Page 384 - Between One and Many The Art and Science of Public Speaking

P. 384

Chapter 13 Informative Speaking 351

Informative Speaking and Persuasion

When you were assigned to read this chapter, it is likely that your instructor also

required you to prepare and deliver an informative speech. When is a speech

primarily informative, as opposed to being persuasive? Depending on whom

you ask, you are likely to get a different answer to this question. Some peo-

ple would argue that a speech can be exclusively informative—with no purpose

other than one person passing information along to an audience. Still others

argue that while the line between what is informative and what is persuasive is

blurred, it is nevertheless there.

Our position is based on a simple premise. An informative speech is not worth

giving unless it is designed to reasonably ensure that it won’t go in one ear and

then right out the other. What good, for example, is an informative speech on

the proper equipment to safely roller blade if it doesn’t increase the probability

of the audience seriously considering the information? Similarly, what good is to

be gained by an informative speech on preventive health practices such as using

sunscreen regularly if it has no motivational value for an audience?

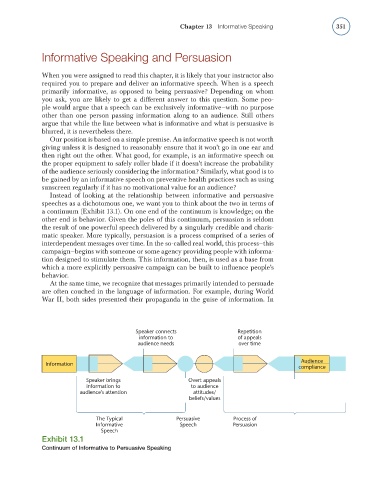

Instead of looking at the relationship between informative and persuasive

speeches as a dichotomous one, we want you to think about the two in terms of

a continuum (Exhibit 13.1). On one end of the continuum is knowledge; on the

other end is behavior. Given the poles of this continuum, persuasion is seldom

the result of one powerful speech delivered by a singularly credible and charis-

matic speaker. More typically, persuasion is a process comprised of a series of

interdependent messages over time. In the so-called real world, this process—this

campaign—begins with someone or some agency providing people with informa-

tion designed to stimulate them. This information, then, is used as a base from

which a more explicitly persuasive campaign can be built to infl uence people’s

behavior.

At the same time, we recognize that messages primarily intended to persuade

are often couched in the language of information. For example, during World

War II, both sides presented their propaganda in the guise of information. In

Speaker connects Repetition

information to of appeals

audience needs over time

Audience

Information

compliance

Speaker brings Overt appeals

information to to audience

audience’s attention attitudes/

beliefs/values

The Typical Persuasive Process of

Informative Speech Persuasion

Speech

Exhibit 13.1

Continuum of Informative to Persuasive Speaking