Page 206 - Biomimetics : Biologically Inspired Technologies

P. 206

Bar-Cohen : Biomimetics: Biologically Inspired Technologies DK3163_c006 Final Proof page 192 21.9.2005 2:56am

192 Biomimetics: Biologically Inspired Technologies

+ 8

Movement 7 Appearance Overall

reaction 2 6 3

1 5 1

1

0 5

0 4 100% similarity to human 2 3 4 100% 1 Toy robot 2 100%

− 1 Industrial robot 3 1 Stuffed toy 2 Uncanny valley

3 Bunraku puppet

2 Android

3 Moving corpse/uncanny valley 2 Non mask of thin man

4 Prorthetic hand 3 Corpse/uncanny valley

5 Handicapped person 4 Decorative robot

5 Doll

6 Bunraku puppet

7 Unhealthy person

8 Healthy person

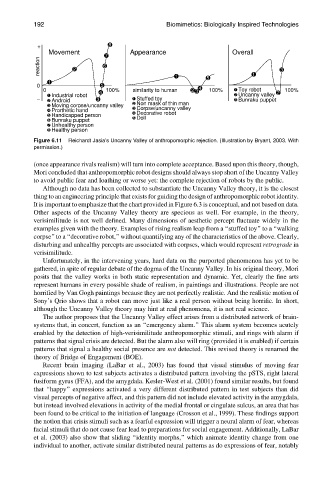

Figure 6.11 Reichardt Jasia’s Uncanny Valley of anthropomorphic rejection. (Illustration by Bryant, 2003. With

permission.)

(once appearance rivals realism) will turn into complete acceptance. Based upon this theory, though,

Mori concluded that anthropomorphic robot designs should always stop short of the Uncanny Valley

to avoid public fear and loathing or worse yet: the complete rejection of robots by the public.

Although no data has been collected to substantiate the Uncanny Valley theory, it is the closest

thing to an engineering principle that exists for guiding the design of anthropomorphic robot identity.

It is important to emphasize that the chart provided in Figure 6.3 is conceptual, and not based on data.

Other aspects of the Uncanny Valley theory are specious as well. For example, in the theory,

verisimilitude is not well defined. Many dimensions of aesthetic percept fluctuate widely in the

examples given with the theory. Examples of rising realism leap from a ‘‘stuffed toy’’ to a ‘‘walking

corpse’’ to a ‘‘decorative robot,’’ without quantifying any of the characteristics of the above. Clearly,

disturbing and unhealthy percepts are associated with corpses, which would represent retrograde in

verisimilitude.

Unfortunately, in the intervening years, hard data on the purported phenomenon has yet to be

gathered, in spite of regular debate of the dogma of the Uncanny Valley. In his original theory, Mori

posits that the valley works in both static representation and dynamic. Yet, clearly the fine arts

represent humans in every possible shade of realism, in paintings and illustrations. People are not

horrified by Van Gogh paintings because they are not perfectly realistic. And the realistic motion of

Sony’s Qrio shows that a robot can move just like a real person without being horrific. In short,

although the Uncanny Valley theory may hint at real phenomena, it is not real science.

The author proposes that the Uncanny Valley effect arises from a distributed network of brain-

systems that, in concert, function as an ‘‘emergency alarm.’’ This alarm system becomes acutely

enabled by the detection of high-verisimilitude anthropomorphic stimuli, and rings with alarm if

patterns that signal crisis are detected. But the alarm also will ring (provided it is enabled) if certain

patterns that signal a healthy social presence are not detected. This revised theory is renamed the

theory of Bridge of Engagement (BOE).

Recent brain imaging (LaBar et al., 2003) has found that visual stimulus of moving fear

expressions shown to test subjects activates a distributed pattern involving the pSTS, right lateral

fusiform gyrus (FFA), and the amygdala. Kesler-West et al. (2001) found similar results, but found

that ‘‘happy’’ expressions activated a very different distributed pattern in test subjects than did

visual percepts of negative affect, and this pattern did not include elevated activity in the amygdala,

but instead involved elevations in activity of the medial frontal or cingulate sulcus, an area that has

been found to be critical to the initiation of language (Crosson et al., 1999). These findings support

the notion that crisis stimuli such as a fearful expression will trigger a neural alarm of fear, whereas

facial stimuli that do not cause fear lead to preparations for social engagement. Additionally, LaBar

et al. (2003) also show that sliding ‘‘identity morphs,’’ which animate identity change from one

individual to another, activate similar distributed neural patterns as do expressions of fear, notably