Page 205 - Cultural Theory and Popular Culture an Introduction

P. 205

CULT_C09.qxd 10/24/08 17:25 Page 189

Jean Baudrillard 189

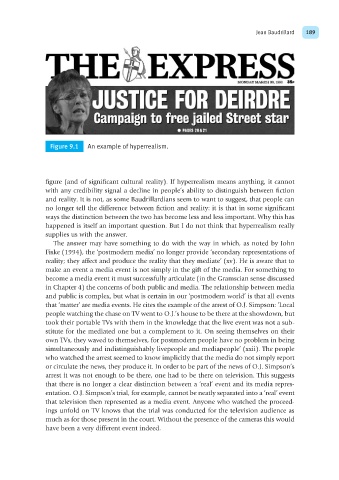

Figure 9.1 An example of hyperrealism.

figure (and of significant cultural reality). If hyperrealism means anything, it cannot

with any credibility signal a decline in people’s ability to distinguish between fiction

and reality. It is not, as some Baudrillardians seem to want to suggest, that people can

no longer tell the difference between fiction and reality: it is that in some significant

ways the distinction between the two has become less and less important. Why this has

happened is itself an important question. But I do not think that hyperrealism really

supplies us with the answer.

The answer may have something to do with the way in which, as noted by John

Fiske (1994), the ‘postmodern media’ no longer provide ‘secondary representations of

reality; they affect and produce the reality that they mediate’ (xv). He is aware that to

make an event a media event is not simply in the gift of the media. For something to

become a media event it must successfully articulate (in the Gramscian sense discussed

in Chapter 4) the concerns of both public and media. The relationship between media

and public is complex, but what is certain in our ‘postmodern world’ is that all events

that ‘matter’ are media events. He cites the example of the arrest of O.J. Simpson: ‘Local

people watching the chase on TV went to O.J.’s house to be there at the showdown, but

took their portable TVs with them in the knowledge that the live event was not a sub-

stitute for the mediated one but a complement to it. On seeing themselves on their

own TVs, they waved to themselves, for postmodern people have no problem in being

simultaneously and indistinguishably livepeople and mediapeople’ (xxii). The people

who watched the arrest seemed to know implicitly that the media do not simply report

or circulate the news, they produce it. In order to be part of the news of O.J. Simpson’s

arrest it was not enough to be there, one had to be there on television. This suggests

that there is no longer a clear distinction between a ‘real’ event and its media repres-

entation. O.J. Simpson’s trial, for example, cannot be neatly separated into a ‘real’ event

that television then represented as a media event. Anyone who watched the proceed-

ings unfold on TV knows that the trial was conducted for the television audience as

much as for those present in the court. Without the presence of the cameras this would

have been a very different event indeed.