Page 282 - Petroleum Geology

P. 282

257

These difficulties account for the rather loose usage of the term “reef” in

subsurface geological work, with the common term “reef complex” allowing

ignorance of detail. It must never be forgotten that the terminology of petro-

leum geology must take the practical side into account: a “lump” revealed

by seismic reflection survey may be termed a reef prospect long before it is

drilled. We shall therefore use the term reef for any reef or reef-like carbonate

body, acknowledging that careful studies can lead to better definitions in

some areas - notably in the Devonian reefs of the Western Canada basin,

studied by so many workers (e.g., Barss et al., 1970; Hemphill et al., 1970;

Hriskevich et al., 1980).

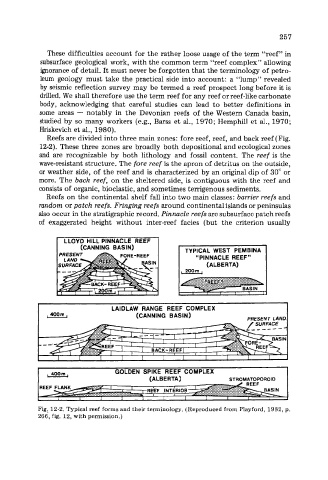

Reefs are divided into three main zones: fore reef, reef, and back reef (Fig.

12-2). These three zones are broadly both depositional and ecological zones

and are recognizable by both lithology and fossil content. The reef is the

wave-resistant structure. The fore reef is the apron of detritus on the outside,

or weather side, of the reef and is characterized by an original dip of 30” or

more. The back reef, on the sheltered side, is contiguous with the reef and

consists of organic, bioclastic, and sometimes terrigenous sediments.

Reefs on the continental shelf fall into two main classes: barrier reefs and

random or patch reefs. Fringing reefs around continental islands or peninsulas

also occur in the stratigraphic record. Pinnacle reefs are subsurface patch reefs

of exaggerated height without inter-reef facies (but the criterion usually

LLOYD HILL PINNACLE REEF

*- “PINNACLE REEF”

(CANNING BASIN) TYPICAL WEST PEMBINA

(ALBERTA)

(CANNING BASIN)

_----

Fig., 12-2. Typical reef forms and their terminology. (Reproduced from Playford, 1982, p.

266, fig. 12, with permission.)