Page 160 -

P. 160

DOMAIN MODELING OF OBJECT-ORIENTED INFORMATION SYSTEMS 145

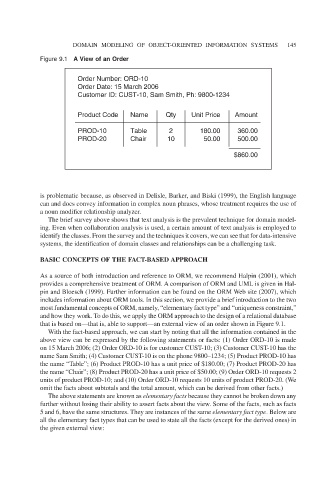

Figure 9.1 A View of an Order

Order Number: ORD-10

Order Date: 15 March 2006

Customer ID: CUST-10, Sam Smith, Ph: 9800-1234

Product Code Name Qty Unit Price Amount

PROD-10 Table 2 180.00 360.00

PROD-20 Chair 10 50.00 500.00

$860.00

is problematic because, as observed in Delisle, Barker, and Biski (1999), the English language

can and does convey information in complex noun phrases, whose treatment requires the use of

a noun modifier relationship analyzer.

The brief survey above shows that text analysis is the prevalent technique for domain model-

ing. Even when collaboration analysis is used, a certain amount of text analysis is employed to

identify the classes. From the survey and the techniques it covers, we can see that for data-intensive

systems, the identification of domain classes and relationships can be a challenging task.

BASIC CONCEPTS OF THE FACT-BASED APPROACH

As a source of both introduction and reference to ORM, we recommend Halpin (2001), which

provides a comprehensive treatment of ORM. A comparison of ORM and UML is given in Hal-

pin and Bloesch (1999). Further information can be found on the ORM Web site (2007), which

includes information about ORM tools. In this section, we provide a brief introduction to the two

most fundamental concepts of ORM, namely, “elementary fact type” and “uniqueness constraint,”

and how they work. To do this, we apply the ORM approach to the design of a relational database

that is based on—that is, able to support—an external view of an order shown in Figure 9.1.

With the fact-based approach, we can start by noting that all the information contained in the

above view can be expressed by the following statements or facts: (1) Order ORD-10 is made

on 15 March 2006; (2) Order ORD-10 is for customer CUST-10; (3) Customer CUST-10 has the

name Sam Smith; (4) Customer CUST-10 is on the phone 9800–1234; (5) Product PROD-10 has

the name “Table”; (6) Product PROD-10 has a unit price of $180.00; (7) Product PROD-20 has

the name “Chair”; (8) Product PROD-20 has a unit price of $50.00; (9) Order ORD-10 requests 2

units of product PROD-10; and (10) Order ORD-10 requests 10 units of product PROD-20. (We

omit the facts about subtotals and the total amount, which can be derived from other facts.)

The above statements are known as elementary facts because they cannot be broken down any

further without losing their ability to assert facts about the view. Some of the facts, such as facts

5 and 6, have the same structures. They are instances of the same elementary fact type. Below are

all the elementary fact types that can be used to state all the facts (except for the derived ones) in

the given external view: