Page 35 - Water and Wastewater Engineering Design Principles and Practice

P. 35

1-6 WATER AND WASTEWATER ENGINEERING

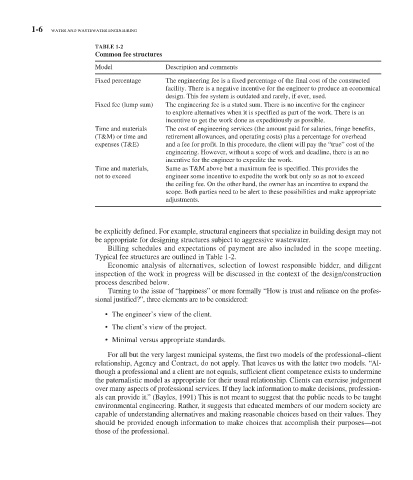

TABLE 1-2

Common fee structures

Model Description and comments

Fixed percentage The engineering fee is a fixed percentage of the final cost of the constructed

facility. There is a negative incentive for the engineer to produce an economical

design. This fee system is outdated and rarely, if ever, used.

Fixed fee (lump sum) The engineering fee is a stated sum. There is no incentive for the engineer

to explore alternatives when it is specified as part of the work. There is an

incentive to get the work done as expeditiously as possible.

Time and materials The cost of engineering services (the amount paid for salaries, fringe benefits,

(T&M) or time and retirement allowances, and operating costs) plus a percentage for overhead

expenses (T&E) and a fee for profit. In this procedure, the client will pay the “true” cost of the

engineering. However, without a scope of work and deadline, there is an no

incentive for the engineer to expedite the work.

Time and materials, Same as T&M above but a maximum fee is specified. This provides the

not to exceed engineer some incentive to expedite the work but only so as not to exceed

the ceiling fee. On the other hand, the owner has an incentive to expand the

scope. Both parties need to be alert to these possibilities and make appropriate

adjustments.

be explicitly defined. For example, structural engineers that specialize in building design may not

be appropriate for designing structures subject to aggressive wastewater.

Billing schedules and expectations of payment are also included in the scope meeting.

Typical fee structures are outlined in Table 1-2 .

Economic analysis of alternatives, selection of lowest responsible bidder, and diligent

inspection of the work in progress will be discussed in the context of the design/construction

process described below.

Turning to the issue of “happiness” or more formally “How is trust and reliance on the profes-

sional justified?”, three elements are to be considered:

• The engineer’s view of the client.

• The client’s view of the project.

• Minimal versus appropriate standards.

For all but the very largest municipal systems, the first two models of the professional–client

relationship, Agency and Contract, do not apply. That leaves us with the latter two models. “Al-

though a professional and a client are not equals, sufficient client competence exists to undermine

the paternalistic model as appropriate for their usual relationship. Clients can exercise judgement

over many aspects of professional services. If they lack information to make decisions, profession-

als can provide it.” (Bayles, 1991) This is not meant to suggest that the public needs to be taught

environmental engineering. Rather, it suggests that educated members of our modern society are

capable of understanding alternatives and making reasonable choices based on their values. They

should be provided enough information to make choices that accomplish their purposes—not

those of the professional.