Page 242 - Moving the Earth_ The Workbook of Excavation

P. 242

DITCHING AND DEWATERING

5.44 THE WORK

In soils that will stand on steep slopes, ditches are the most economical construction down to

a depth of a few feet. When wide cuts must be made to produce stable slopes, or when greater

depth is required, the open ditch may involve so much excavation as to be more costly than tile.

Ditches, together with any space required for spoil, may occupy rather wide strips of land. If in

farms, they cut up the fields and add to the expense of planting and cultivation. They are hazardous

when near roads. In any location, they will require occasional culverts or bridges for crossings.

Ditches usually require maintenance. This may include removing silt and cave-ins, repairing

erosion damage, and cleaning out vegetation. Neglect may result in general deterioration, with

eventual stoppage, or expensive redigging and clearing.

Buried drains do not cut up the fields, or offer hazards along roadsides. However, if one

becomes plugged, as a result of poor design, improper installation, or accident, it may be difficult

and expensive to locate the difficulty. If the stoppage is due to general silting, it will probably be

cheaper to lay a new line than to dig up and clean or repair the old one.

Choice of the type of drainage will depend on local conditions and on individual judgment.

Water slope. The porosity and bedding of the soil largely determine the depth and spacing and

to some extent the size of drains required for a given project.

A pool of surface water will assume a slight but measurable slope from its inlet down to an

outlet or drain. If the pool is choked with weeds and brush, water may be removed more rapidly

than it can flow through the obstructions, so the level at the drain may be several inches below

that at other parts of the pond as long as flow continues.

The water table may be considered to be the surface of an underground pond, obstructed in its

flow by soil particles. If these particles are coarse and loosely fitted, the spaces will be large enough

to allow some freedom of flow, and the slope up from an outlet of the water surface will be gradual.

If the soil is fine-grained and compact, the spaces will be so small that flow will be almost stopped

and the gradient down to a drain point will be very steep. This slope is called the hydraulic gradient.

Slopes will usually be steeper after rains and in wet seasons than when the surface is dry.

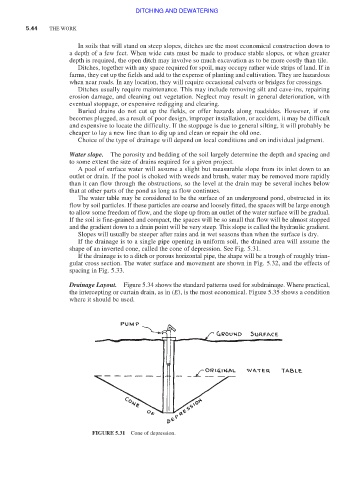

If the drainage is to a single pipe opening in uniform soil, the drained area will assume the

shape of an inverted cone, called the cone of depression. See Fig. 5.31.

If the drainage is to a ditch or porous horizontal pipe, the shape will be a trough of roughly trian-

gular cross section. The water surface and movement are shown in Fig. 5.32, and the effects of

spacing in Fig. 5.33.

Drainage Layout. Figure 5.34 shows the standard patterns used for subdrainage. Where practical,

the intercepting or curtain drain, as in (E), is the most economical. Figure 5.35 shows a condition

where it should be used.

FIGURE 5.31 Cone of depression.