Page 322 -

P. 322

11.2 CHAPTER ELEVEN

Total hardness is usually defined as simply the sum of magnesium and calcium hard-

ness in milligrams per liter as CaCO3. Total hardness can also be differentiated into car-

bonate and noncarbonate hardness. Carbonate hardness is the portion of total hardness

present in the form of bicarbonate salts [Ca(HCO3)2 and Mg(HCO3)2] and carbonate com-

pounds (CaCO3 and MgCO3). Noncarbonate hardness is the portion of calcium and mag-

nesium present as noncarbonate salts, such as calcium sulfate (CaSO4), calcium chloride

(CaC12), magnesium sulfate (MgSO4), and magnesium chloride (MgC1). The sum of car-

bonate and noncarbonate hardness equals total hardness.

Acceptable Level of Hardness

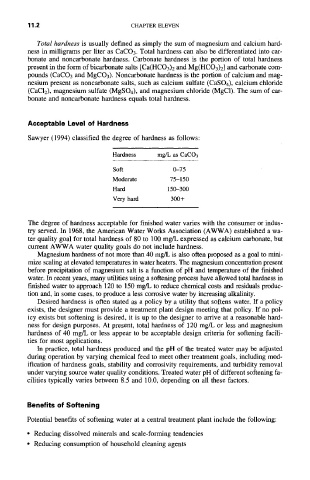

Sawyer (1994) classified the degree of hardness as follows:

Hardness mg/L as CaCO 3

Soft 0-75

Moderate 75-150

Hard 150-300

Very hard 300 +

The degree of hardness acceptable for finished water varies with the consumer or indus-

try served. In 1968, the American Water Works Association (AWWA) established a wa-

ter quality goal for total hardness of 80 to 100 mg/L expressed as calcium carbonate, but

current AWWA water quality goals do not include hardness.

Magnesium hardness of not more than 40 mg/L is also often proposed as a goal to mini-

mize scaling at elevated temperatures in water heaters. The magnesium concentration present

before precipitation of magnesium salt is a function of pH and temperature of the fmished

water. In recent years, many utilities using a softening process have allowed total hardness in

finished water to approach 120 to 150 mg/L to reduce chemical costs and residuals produc-

tion and, in some cases, to produce a less corrosive water by increasing alkalinity.

Desired hardness is often stated as a policy by a utility that softens water. If a policy

exists, the designer must provide a treatment plant design meeting that policy. If no pol-

icy exists but softening is desired, it is up to the designer to arrive at a reasonable hard-

ness for design purposes. At present, total hardness of 120 mg/L or less and magnesium

hardness of 40 mg/L or less appear to be acceptable design criteria for softening facili-

ties for most applications.

In practice, total hardness produced and the pH of the treated water may be adjusted

during operation by varying chemical feed to meet other treatment goals, including mod-

ification of hardness goals, stability and corrosivity requirements, and turbidity removal

under varying source water quality conditions. Treated water pH of different softening fa-

cilities typically varies between 8.5 and 10.0, depending on all these factors.

Benefits of Softening

Potential benefits of softening water at a central treatment plant include the following:

• Reducing dissolved minerals and scale-forming tendencies

• Reducing consumption of household cleaning agents