Page 42 - An Atlas of Carboniferous Basin Evolution in Northern England

P. 42

Carboniferous basin development 23

Evans & Kirby 1999). These facies and thickness variations indicate a southern

fault-bounded basin margin situated at depth below the inversion-related

Pendle Monocline (Fig. 18), with carbonate platform margins developed in the

Chadian, Arundian and Asbian/Brigantian (Evans & Kirby 1999). The

northern margin of the basin is marked by facies and thickness changes on

to the Bowland High (Gawthorpe 1987a; Lawrence et al 1987; Arthurton et al.

1988) and the Askrigg Block (Tiddeman 1889; Hudson 1930).

Within the basin, basement has not been penetrated by any borehole to date,

the oldest proven sediments being of Courceyan age (EClb). These were

penetrated by the Swinden borehole and comprise sub-wavebase, argillaceous

packstones deposited on the distal portion of a carbonate ramp (Gawthorpe et

al. 1989). This general style of sedimentation continued into the Chadian (EC2;

Chatburn and Thornton Limestones). Thickness and facies variations indicate

some degree of structural control which was inherited from earlier late

Devonian-Courceyan (ECl) rifting. Waulsortian carbonate buildups are often

associated with the flanks of intra-basinal fault blocks (Miller & Grayson 1982;

Lees & Miller 1985) that formed the sites of major Variscan inversion

structures (e.g. Clitheroe, Hetton-Eshton and Slaidburn anticlines; Arthurton

1984; Gawthorpe 1987a; Arthurton et al 1988).

The late Chadian-Holkerian (EC3) was marked by the rapid development of

sea-floor topography, indicated by thickness and facies differentiation across

the basin (Gawthorpe 1987a). This topography was associated with reactiva-

tion of extensional faults and the development of local footwall unconformities

within the basin. The succession in the basin became dominated by mudstones

(Worston Shales) with local developments of siliciclastic turbidites and

sedimentary slides (Gawthorpe & Clemmey 1985). In addition Pb-Zn

mineralization is associated with these events (Gawthorpe et al. 1989). The

succeeding Holkerian to early Asbian (EC4) shows a progressive increase in

carbonate sedimentation, culminating in the development of carbonate-

rimmed shelves along the northern margin of the basin.

A further phase of tectonism occurred during the late Asbian to early

Brigantian (EC5) (Gawthorpe 1986). This phase, which comprised several

events, is characterized by major units of resedimented carbonate conglom-

erate, the common occurrence of soft sediment deformation features and major

facies and thickness variations within the basin and across the northern basin

margin. Background sedimentation became dominated by deep marine

mudstone (Bowland Shales) with influxes of coarse grained siliciclastic

turbidites (mid-Brigantian Pendleside Sandstone). Facies distributions and

thickness variations indicate southerly downthrow on the Middle Craven

Fault. However, slip reversal along this fault in the Brigantian may be

indicated by uplift and erosion of carbonate buildups in the hanging-wall

(Mundy 1980).

Namurian and Westphalian strata are some 2 km thick in the syncline that

separates the Pendle Monocline from the Rossendale High (Lancashire

Coalfield), and about 1500 m in the Holme Chapel and Boulsworth boreholes

(Fig. 18). There is no direct evidence for original thicknesses over the central

part of the basin, but they are likely to have been in excess of the preserved

2km. Pendleian facies are typical Millstone Grits and Coal Measures,

pervasive over this part of the central Pennine Basin. However, the initial

clastic infill of delta-front turbidites (the Pendleian aged Pendle Grit; LC1 a) is

much older than in the East Midlands (e.g. Widmerpool Gulf).

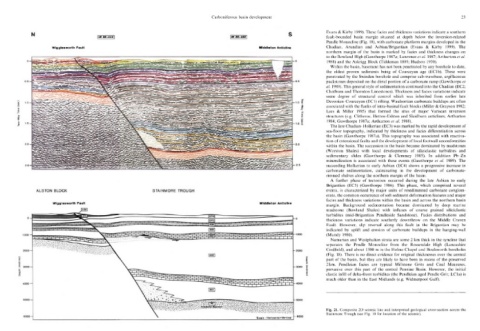

Fig. 21. Composite 2D seismic line and interpreted geological cross-section across the

Stainmore Trough (see Fig. 10 for location of the seismic).