Page 191 - Carbonate Facies in Geologic History

P. 191

178 Pennsylvanian-Lower Permian Shelf Margin Facies

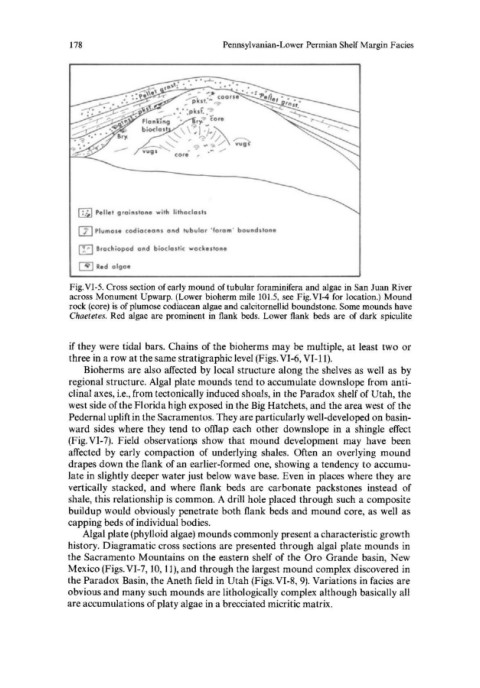

~ P.II.t g,ainstone with lithoclas ..

rn Plumose codiaceans ond tubula, 'foram' boundstone

Il:::J B,achiopod and bioclastic wackestone

~ Red olgae

Fig. VI-5. Cross section of early mound of tubular foraminifera and algae in San Juan River

across Monument Upwarp. (Lower bioherm mile 101.5, see Fig. VI-4 for location.) Mound

rock (core) is of plumose codiacean algae and calcitornellid boundstone. Some mounds have

Chaetetes. Red algae are prominent in flank beds. Lower flank beds are of dark spiculite

if they were tidal bars. Chains of the bioherms may be multiple, at least two or

three in a row at the same stratigraphic level (Figs. VI-6, VI-11).

Bioherms are also affected by local structure along the shelves as well as by

regional structure. Algal plate mounds tend to accumulate downslope from anti-

clinal axes, i.e., from tectonically induced shoals, in the Paradox shelf of Utah, the

west side ofthe Florida high exposed in the Big Hatchets, and the area west of the

Pedernal uplift in the Sacramentos. They are particularly well-developed on basin-

ward sides where they tend to offlap each other downslope in a shingle effect

(Fig. VI-7). Field observatiOI'\S show that mound development may have been

affected by early compaction of underlying shales. Often an overlying mound

drapes down the flank of an earlier-formed one, showing a tendency to accumu-

late in slightly deeper water just below wave base. Even in places where they are

vertically stacked, and where flank beds are carbonate packstones instead of

shale, this relationship is common. A drill hole placed through such a composite

buildup would obviously penetrate both flank beds and mound core, as well as

capping beds of individual bodies.

Algal plate (phylloid algae) mounds commonly present a characteristic growth

history. Diagramatic cross sections are presented through algal plate mounds in

the Sacramento Mountains on the eastern shelf of the Oro Grande basin, New

Mexico (Figs. VI-7, 10, 11), and through the largest mound complex discovered in

the Paradox Basin, the Aneth field in Utah (Figs. VI-8, 9). Variations in facies are

obvious and many such mounds are lithologically complex although basically all

are accumulations of platy algae in a brecciated micritic matrix.