Page 380 - Carbonate Facies in Geologic History

P. 380

Mound Facies Sequence 367

~ Organ ic yeneer

. . . . .. .

o· .... • •

..

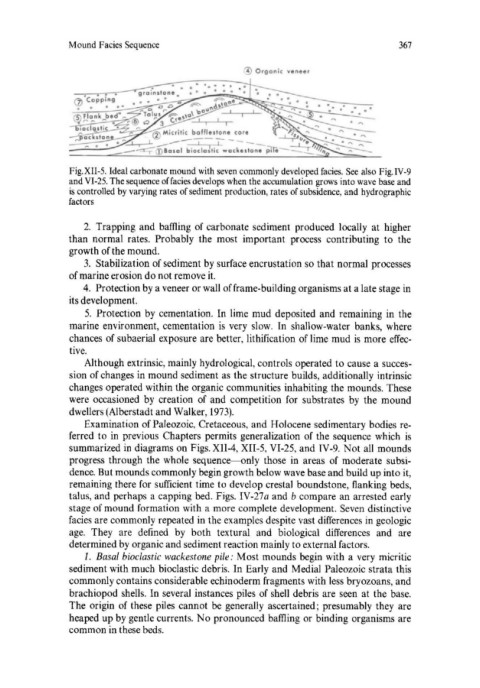

Fig.XlI-S. Ideal carbonate mound with seven commonly developed facies. See also Fig.IV-9

and VI-2S. The sequence offacies develops when the accumulation grows into wave base and

is controlled by varying rates of sediment production, rates of subsidence, and hydrographic

factors

2. Trapping and baffling of carbonate sediment produced locally at higher

than normal rates. Probably the most important process contributing to the

growth of the mound.

3. Stabilization of sediment by surface encrustation so that normal processes

of marine erosion do not remove it.

4. Protection by a veneer or wall of frame-building organisms at a late stage in

its development.

S. Protection by cementation. In lime mud deposited and remaining in the

marine environment, cementation is very slow. In shallow-water banks, where

chances of subaerial exposure are better, lithification of lime mud is more effec-

tive.

Although extrinsic, mainly hydrological, controls operated to cause a succes-

sion of changes in mound sediment as the structure builds, additionally intrinsic

changes operated within the organic communities inhabiting the mounds. These

were occasioned by creation of and competition for substrates by the mound

dwellers (Alber stadt and Walker, 1973).

Examination of Paleozoic, Cretaceous, and Holocene sedimentary bodies re-

ferred to in previous Chapters permits generalization of the sequence which is

summarized in diagrams on Figs. XII-4, XII-S, VI-2S, and IV-9. Not all mounds

progress through the whole sequence--only those in areas of moderate subsi-

dence. But mounds commonly begin growth below wave base and build up into it,

remaining there for sufficient time to develop crestal boundstone, flanking beds,

talus, and perhaps a capping bed. Figs. IV -27 a and b compare an arrested early

stage of mound formation with a more complete development. Seven distinctive

facies are commonly repeated in the examples despite vast differences in geologic

age. They are defined by both textural and biological differences and are

determined by organic and sediment reaction mainly to external factors.

1. Basal bioclastic wackestone pile: Most mounds begin with a very micritic

sediment with much bioclastic debris. In Early and Medial Paleozoic strata this

commonly contains considerable echinoderm fragments with less bryozoans, and

brachiopod shells. In several instances piles of shell debris are seen at the base.

The origin of these piles cannot be generally ascertained; presumably they are

heaped up by gentle currents. No pronounced baffling or binding organisms are

common in these beds.