Page 167 - Earth's Climate Past and Future

P. 167

CHAPTER 8 • Insolation Control of Monsoons 143

of salty water along the northern margins of the hypothesis (see Figure 8-5). The close match indicates

Mediterranean during incursions of cold air from the some kind of connection to the low-latitude monsoon

north. These two factors make surface waters dense over North Africa.

enough to sink to great depths. The dense waters that Initially some climate scientists questioned this

sink deep into the Mediterranean Sea eventually exit explanation. The Mediterranean Sea lies at high sub-

westward into the Atlantic Ocean. As a result of this tropical latitudes (30°–40°N), beyond even the greatest

flow, the floor of today’s Mediterranean Sea is covered northward expansions of past summer monsoons indi-

by sediments typical of well-oxygenated ocean basins: cated by lake-level evidence across North Africa. If cli-

light tan silty mud containing shells of plankton that mate within the confines of the Mediterranean region

once lived at the sea surface and benthic foraminifera never became truly monsoonal, how could the stinky

that once lived on the seafloor. muds deposited in that basin be a response to the North

Mediterranean sediments also contain occasional African monsoon?

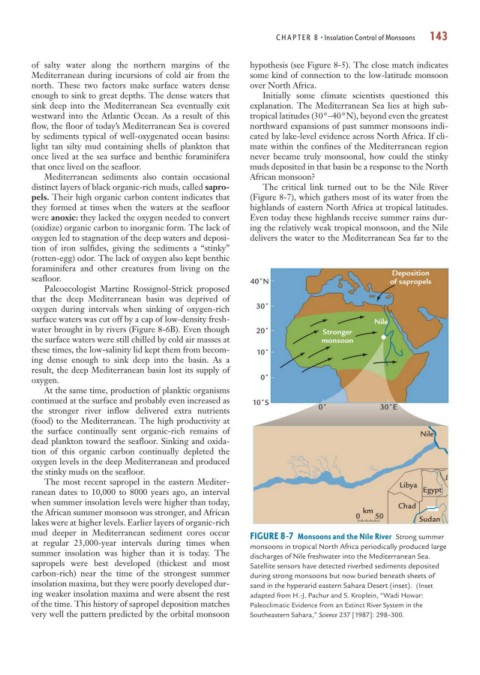

distinct layers of black organic-rich muds, called sapro- The critical link turned out to be the Nile River

pels. Their high organic carbon content indicates that (Figure 8-7), which gathers most of its water from the

they formed at times when the waters at the seafloor highlands of eastern North Africa at tropical latitudes.

were anoxic: they lacked the oxygen needed to convert Even today these highlands receive summer rains dur-

(oxidize) organic carbon to inorganic form. The lack of ing the relatively weak tropical monsoon, and the Nile

oxygen led to stagnation of the deep waters and deposi- delivers the water to the Mediterranean Sea far to the

tion of iron sulfides, giving the sediments a “stinky”

(rotten-egg) odor. The lack of oxygen also kept benthic

foraminifera and other creatures from living on the Deposition

seafloor. 40˚N of sapropels

Paleoecologist Martine Rossignol-Strick proposed

that the deep Mediterranean basin was deprived of

oxygen during intervals when sinking of oxygen-rich 30˚

surface waters was cut off by a cap of low-density fresh- Nile

water brought in by rivers (Figure 8-6B). Even though 20˚ Stronger

the surface waters were still chilled by cold air masses at monsoon

these times, the low-salinity lid kept them from becom- 10˚

ing dense enough to sink deep into the basin. As a

result, the deep Mediterranean basin lost its supply of

oxygen. 0˚

At the same time, production of planktic organisms

continued at the surface and probably even increased as 10˚S

the stronger river inflow delivered extra nutrients 0˚ 30˚E

(food) to the Mediterranean. The high productivity at

the surface continually sent organic-rich remains of Nile

dead plankton toward the seafloor. Sinking and oxida-

tion of this organic carbon continually depleted the

oxygen levels in the deep Mediterranean and produced

the stinky muds on the seafloor.

The most recent sapropel in the eastern Mediter- Libya

ranean dates to 10,000 to 8000 years ago, an interval Egypt

when summer insolation levels were higher than today, Chad

the African summer monsoon was stronger, and African 0 km 50

lakes were at higher levels. Earlier layers of organic-rich Sudan

mud deeper in Mediterranean sediment cores occur FIGURE 8-7 Monsoons and the Nile River Strong summer

at regular 23,000-year intervals during times when monsoons in tropical North Africa periodically produced large

summer insolation was higher than it is today. The discharges of Nile freshwater into the Mediterranean Sea.

sapropels were best developed (thickest and most Satellite sensors have detected riverbed sediments deposited

carbon-rich) near the time of the strongest summer during strong monsoons but now buried beneath sheets of

insolation maxima, but they were poorly developed dur- sand in the hyperarid eastern Sahara Desert (inset). (Inset

ing weaker insolation maxima and were absent the rest adapted from H.-J. Pachur and S. Kroplein, “Wadi Howar:

of the time. This history of sapropel deposition matches Paleoclimatic Evidence from an Extinct River System in the

very well the pattern predicted by the orbital monsoon Southeastern Sahara,” Science 237 [1987]: 298–300.