Page 307 - Envoys and Political Communication in the Late Antique West 411 - 533

P. 307

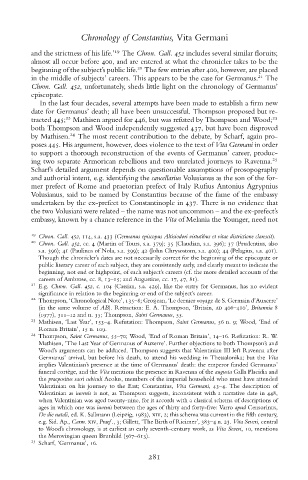

Chronology of Constantius, Vita Germani

19

and the strictness of his life.’ The Chron. Gall. 452 includes several similar floruits;

almostall occur before 400, and are entered at what the chronicler takes to be the

20

beginning of the subject’s public life. The few entries after 400, however, are placed

21

in the middle of subjects’ careers. This appears to be the case for Germanus. The

Chron. Gall. 452, unfortunately, sheds little light on the chronology of Germanus’

episcopate.

In the last four decades, several attempts have been made to establish a firm new

date for Germanus’ death; all have been unsuccessful. Thompson proposed but re-

22

tracted 445; Mathisen argued for 446, butwas refuted by Thompson and Wood; 23

both Thompson and Wood independently suggested 437, buthave been disproved

by Mathisen. 24 The most recent contribution to the debate, by Scharf, again pro-

poses 445. His argument, however, does violence to the text of Vita Germani in order

to support a thorough reconstruction of the events of Germanus’ career, produc-

ing two separate Armorican rebellions and two unrelated journeys to Ravenna. 25

Scharf’s detailed argument depends on questionable assumptions of prosopography

and authorial intent, e.g. identifying the cancellarius Volusianus as the son of the for-

mer prefect of Rome and praetorian prefect of Italy Rufius Antonius Agrypnius

Volusianus, said to be named by Constantius because of the fame of the embassy

undertaken by the ex-prefect to Constantinople in 437. There is no evidence that

the two Volusiani were related – the name was not uncommon – and the ex-prefect’s

embassy, known by a chance reference in the Vita of Melania the Younger, need not

19

Chron. Gall. 452, 114, s.a. 433 (Germanus episcopus Altisiodori virtutibus et vitae districtione clarescit).

20

Chron. Gall. 452,cc. 4 (Martin of Tours, s.a. 379); 35 (Claudian, s.a. 396); 37 (Prudentius, also

s.a. 396); 41 (Paulinus of Nola, s.a. 399); 42 (John Chrysostom, s.a. 400); 44 (Pelagius, s.a. 401).

Though the chronicler’s dates are not necessarily correct for the beginning of the episcopate or

public literary career of each subject, they are consistently early, and clearly meant to indicate the

beginning, not end or highpoint, of each subject’s careers (cf. the more detailed accounts of the

careers of Ambrose, cc. 8, 13–15; and Augustine, cc. 17, 47, 81).

21 E.g. Chron. Gall. 452,c. 104 (Cassian, s.a. 429), like the entry for Germanus, has no evident

significance in relation to the beginning or end of the subject’s career.

22 Thompson, ‘Chronological Note’, 135–8; Grosjean, ‘Le dernier voyage de S. Germain d’Auxerre’

(in the same volume of AB). Retraction: E. A. Thompson, ‘Britain, ad 406–410’, Britannia 8

(1977), 311–12 and n. 35; Thompson, Saint Germanus, 55.

23 Mathisen, ‘Last Year’, 153–4. Refutation: Thompson, Saint Germanus, 56 n. 9; Wood, ‘End of

Roman Britain’, 15 n. 109.

24 Thompson, Saint Germanus, 55–70; Wood, ‘End of Roman Britain’, 14–16. Refutation: R. W.

Mathisen, ‘The Last Year of Germanus of Auxerre’. Further objections to both Thompson’s and

Wood’s arguments can be adduced. Thompson suggests that Valentinian III left Ravenna after

Germanus’ arrival, but before his death, to attend his wedding in Thessalonika; but the Vita

implies Valentinian’s presence at the time of Germanus’ death: the emperor funded Germanus’

funeral cort` ege, and the Vita mentions the presence in Ravenna of the augusta Galla Placidia and

the praepositus sacri cubiculi Acolus, members of the imperial household who must have attended

Valentinian on his journey to the East; Constantius, Vita Germani, 43–4. The description of

Valentinian as iuvenis is not, as Thompson suggests, inconsistent with a narrative date in 448,

when Valentinian was aged twenty-nine, for it accords with a classical schema of descriptions of

ages in which one was iuvenis between the ages of thirty and forty-five: Varro apud Censorinus,

De die natali, ed. K. Sallmann (Leipzig, 1983), xiv, 2; this schema was current in the fifth century,

e.g. Sid. Ap., Carm. xiv, Praef ., 3; Gillett, ‘The Birth of Ricimer’, 383–4 n. 23. Vita Severi, central

to Wood’s chronology, is at earliest an early seventh-century work, as Vita Severi, 10, mentions

the Merovingian queen Brunhild (567–613).

25

Scharf, ‘Germanus’, 16.

281