Page 378 - Fair, Geyer, and Okun's Water and wastewater engineering : water supply and wastewater removal

P. 378

JWCL344_ch10_333-356.qxd 8/2/10 9:02 PM Page 338

338 Chapter 10 Introduction to Wastewater Systems

10.2 SYSTEM PATTERNS

Among the factors determining the pattern of collecting systems are the following:

1. Type of system (whether separate or combined)

2. Street lines or rights of way

3. Topography, hydrology, and geology of the drainage area

4. Political boundaries

5. Location and nature of treatment and disposal works.

Storm drains are naturally made to seek the shortest path to existing surface channels.

Combined systems have become rare. They pollute the waters washing the immediate

shores of the community and make domestic wastewater treatment difficult. More often,

their flows are intercepted before they can spill into waters that need to be protected. If the

tributary area is at all large, the capacity of the interceptor should be held to some reason-

able multiple of the average dry-weather flow or to the dry-weather flow plus the first flush

of stormwater, which, understandably, is most heavily polluted. Rainfall intensities and du-

rations are deciding factors. In North America, rainfalls are so intense that the number of

spills cannot be reduced appreciably by raising the capacity of interceptors even to as

much as 10 times the dry-weather flow. No more than the maximum dry-weather flow be-

comes the economically justifiable limit. Domestic wastewater in excess of this amount

spills into the receiving water through outlets that antedate interception, or through

stormwater overflows constructed for this purpose.

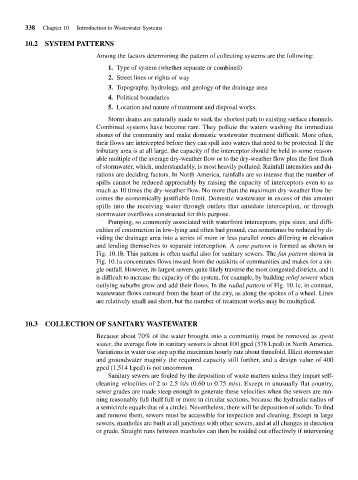

Pumping, so commonly associated with waterfront interceptors, pipe sizes, and diffi-

culties of construction in low-lying and often bad ground, can sometimes be reduced by di-

viding the drainage area into a series of more or less parallel zones differing in elevation

and lending themselves to separate interception. A zone pattern is formed as shown in

Fig. 10.1b. This pattern is often useful also for sanitary sewers. The fan pattern shown in

Fig. 10.1a concentrates flows inward from the outskirts of communities and makes for a sin-

gle outfall. However, its largest sewers quite likely traverse the most congested districts, and it

is difficult to increase the capacity of the system, for example, by building relief sewers when

outlying suburbs grow and add their flows. In the radial pattern of Fig. 10.1c, in contrast,

wastewater flows outward from the heart of the city, as along the spokes of a wheel. Lines

are relatively small and short, but the number of treatment works may be multiplied.

10.3 COLLECTION OF SANITARY WASTEWATER

Because about 70% of the water brought into a community must be removed as spent

water, the average flow in sanitary sewers is about 100 gpcd (378 Lpcd) in North America.

Variations in water use step up the maximum hourly rate about threefold. Illicit stormwater

and groundwater magnify the required capacity still further, and a design value of 400

gpcd (1,514 Lpcd) is not uncommon.

Sanitary sewers are fouled by the deposition of waste matters unless they impart self-

cleaning velocities of 2 to 2.5 ft/s (0.60 to 0.75 m/s). Except in unusually flat country,

sewer grades are made steep enough to generate these velocities when the sewers are run-

ning reasonably full (half full or more in circular sections, because the hydraulic radius of

a semicircle equals that of a circle). Nevertheless, there will be deposition of solids. To find

and remove them, sewers must be accessible for inspection and cleaning. Except in large

sewers, manholes are built at all junctions with other sewers, and at all changes in direction

or grade. Straight runs between manholes can then be rodded out effectively if intervening