Page 383 - Fair, Geyer, and Okun's Water and wastewater engineering : water supply and wastewater removal

P. 383

JWCL344_ch10_333-356.qxd 8/2/10 9:02 PM Page 343

10.6 Choice of Collecting System 343

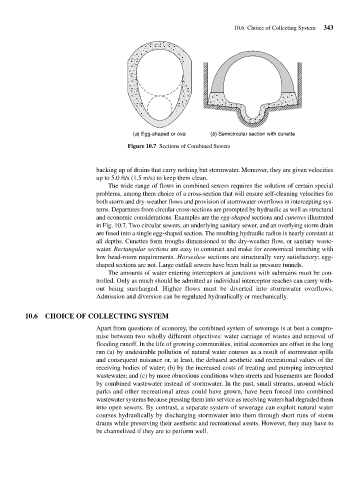

(a) Egg-shaped or oval (b) Semicircular section with cunette

Figure 10.7 Sections of Combined Sewers

backing up of drains that carry nothing but stormwater. Moreover, they are given velocities

up to 5.0 ft/s (1.5 m/s) to keep them clean.

The wide range of flows in combined sewers requires the solution of certain special

problems, among them choice of a cross-section that will ensure self-cleaning velocities for

both storm and dry-weather flows and provision of stormwater overflows in intercepting sys-

tems. Departures from circular cross-sections are prompted by hydraulic as well as structural

and economic considerations. Examples are the egg-shaped sections and cunettes illustrated

in Fig. 10.7. Two circular sewers, an underlying sanitary sewer, and an overlying storm drain

are fused into a single egg-shaped section. The resulting hydraulic radius is nearly constant at

all depths. Cunettes form troughs dimensioned to the dry-weather flow, or sanitary waste-

water. Rectangular sections are easy to construct and make for economical trenching with

low head-room requirements. Horseshoe sections are structurally very satisfactory; egg-

shaped sections are not. Large outfall sewers have been built as pressure tunnels.

The amounts of water entering interceptors at junctions with submains must be con-

trolled. Only as much should be admitted as individual interceptor reaches can carry with-

out being surcharged. Higher flows must be diverted into stormwater overflows.

Admission and diversion can be regulated hydraulically or mechanically.

10.6 CHOICE OF COLLECTING SYSTEM

Apart from questions of economy, the combined system of sewerage is at best a compro-

mise between two wholly different objectives: water carriage of wastes and removal of

flooding runoff. In the life of growing communities, initial economies are offset in the long

run (a) by undesirable pollution of natural water courses as a result of stormwater spills

and consequent nuisance or, at least, the debased aesthetic and recreational values of the

receiving bodies of water; (b) by the increased costs of treating and pumping intercepted

wastewater; and (c) by more obnoxious conditions when streets and basements are flooded

by combined wastewater instead of stormwater. In the past, small streams, around which

parks and other recreational areas could have grown, have been forced into combined

wastewater systems because pressing them into service as receiving waters had degraded them

into open sewers. By contrast, a separate system of sewerage can exploit natural water

courses hydraulically by discharging stormwater into them through short runs of storm

drains while preserving their aesthetic and recreational assets. However, they may have to

be channelized if they are to perform well.