Page 36 -

P. 36

C h a p t e r 1 : h a p t e r 1 :

C O O v e r v i e w a n d I s s u e s v e r v i e w a n d I s s u e s 7 7

raw materials. On the other hand, if they are disposed of improperly, they can be major

sources of toxins and carcinogens.

The problem in many places, including the United States, is that there is no formal,

official, legal process in place for the disposal of electronics. There is no umbrella federal

law, and individual cities have different requirements for the disposal of electronic waste, PART I

but it’s a patchwork at best. Other parts of the globe are doing better. Much of Europe and

PART I

PART I

the whole of Japan have policies in place that govern not only what can go inside computer,

but also how those devices should be handled when they’ve reached their end of life.

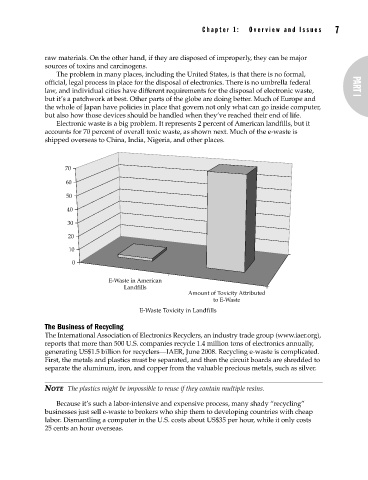

Electronic waste is a big problem. It represents 2 percent of American landfills, but it

accounts for 70 percent of overall toxic waste, as shown next. Much of the e-waste is

shipped overseas to China, India, Nigeria, and other places.

70

60

50

40

30

20

10

0

E-Waste in American

Landfills

Amount of Toxicity Attributed

to E-Waste

E-Waste Toxicity in Landfills

The Business of Recycling

The International Association of Electronics Recyclers, an industry trade group (www.iaer.org),

reports that more than 500 U.S. companies recycle 1.4 million tons of electronics annually,

generating US$1.5 billion for recyclers—IAER, June 2008. Recycling e-waste is complicated.

First, the metals and plastics must be separated, and then the circuit boards are shredded to

separate the aluminum, iron, and copper from the valuable precious metals, such as silver.

NOTE The plastics might be impossible to reuse if they contain multiple resins.

Because it’s such a labor-intensive and expensive process, many shady “recycling”

businesses just sell e-waste to brokers who ship them to developing countries with cheap

labor. Dismantling a computer in the U.S. costs about US$35 per hour, while it only costs

25 cents an hour overseas.