Page 68 - Handbooks of Applied Linguistics Communication Competence Language and Communication Problems Practical Solutions

P. 68

ˇ

46 Vladimir Zegarac

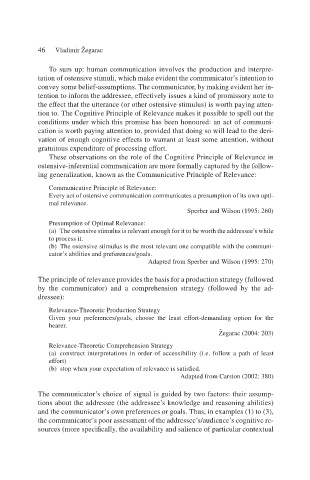

To sum up: human communication involves the production and interpre-

tation of ostensive stimuli, which make evident the communicator’s intention to

convey some belief-assumptions. The communicator, by making evident her in-

tention to inform the addressee, effectively issues a kind of promissory note to

the effect that the utterance (or other ostensive stimulus) is worth paying atten-

tion to. The Cognitive Principle of Relevance makes it possible to spell out the

conditions under which this promise has been honoured: an act of communi-

cation is worth paying attention to, provided that doing so will lead to the deri-

vation of enough cognitive effects to warrant at least some attention, without

gratuitous expenditure of processing effort.

These observations on the role of the Cognitive Principle of Relevance in

ostensive-inferential communication are more formally captured by the follow-

ing generalization, known as the Communicative Principle of Relevance:

Communicative Principle of Relevance:

Every act of ostensive communication communicates a presumption of its own opti-

mal relevance.

Sperber and Wilson (1995: 260)

Presumption of Optimal Relevance:

(a) The ostensive stimulus is relevant enough for it to be worth the addressee’s while

to process it.

(b) The ostensive stimulus is the most relevant one compatible with the communi-

cator’s abilities and preferences/goals.

Adapted from Sperber and Wilson (1995: 270)

The principle of relevance provides the basis for a production strategy (followed

by the communicator) and a comprehension strategy (followed by the ad-

dressee):

Relevance-Theoretic Production Strategy

Given your preferences/goals, choose the least effort-demanding option for the

hearer.

ˇ

Zegarac (2004: 203)

Relevance-Theoretic Comprehension Strategy

(a) construct interpretations in order of accessibility (i.e. follow a path of least

effort)

(b) stop when your expectation of relevance is satisfied.

Adapted from Carston (2002: 380)

The communicator’s choice of signal is guided by two factors: their assump-

tions about the addressee (the addressee’s knowledge and reasoning abilities)

and the communicator’s own preferences or goals. Thus, in examples (1) to (3),

the communicator’s poor assessment of the addressee’s/audience’s cognitive re-

sources (more specifically, the availability and salience of particular contextual