Page 317 - Introduction to Microcontrollers Architecture, Programming, and Interfacing of The Motorola 68HC12

P. 317

294 Chapter 10 Elementary Data Structures

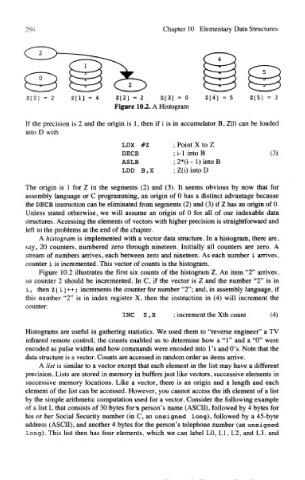

Figure 10.2. A Histogram

If the precision is 2 and the origin is 1, then if i is in accumulator B, Z(i) can be loaded

into D with

LDX #Z ; Point X to Z

DECS ; i-1 into B (3)

ASLB ; 2*(i - 1) into B

LDD B f X ;Z(i)intoD

The origin is 1 for Z in the segments (2) and (3). It seems obvious by now that for

assembly language or C programming, an origin of 0 has a distinct advantage because

the DECS instruction can be eliminated from segments (2) and (3) if Z has an origin of 0.

Unless stated otherwise, we will assume an origin of 0 for all of our indexable data

structures. Accessing the elements of vectors with higher precision is straightforward and

left to the problems at the end of the chapter.

A histogram is implemented with a vector data structure. In a histogram, there are,

say, 20 counters, numbered zero through nineteen. Initially all counters are zero. A

stream of numbers arrives, each between zero and nineteen. As each number i arrives,

counter i is incremented. This vector of counts is the histogram.

Figure 10.2 illustrates the first six counts of the histogram Z, An item "2" arrives,

so counter 2 should be incremented. In C, if the vector is Z and the number "2" is in

i, then z [ i]++; increments the counter for number "2"; and, in assembly language, if

this number "2" is in index register X, then the instruction in (4) will increment the

counter:

INC Z, X ; increment the Xth count (4)

Histograms are useful in gathering statistics. We used them to "reverse engineer" a TV

infrared remote control; the counts enabled us to determine how a "1" and a "0" were

encoded as pulse widths and how commands were encoded into 1 's and O's. Note that the

data structure is a vector. Counts are accessed in random order as items arrive.

A list is similar to a vector except that each element in the list may have a different

precision. Lists are stored in memory in buffers just like vectors, successive elements in

successive memory locations. Like a vector, there is an origin and a length and each

element of the list can be accessed. However, you cannot access the ith element of a list

by the simple arithmetic computation used for a vector. Consider the following example

of a list L that consists of 30 bytes for*a person's name (ASCII), followed by 4 bytes for

his or her Social Security number (in C, an unsigned long), followed by a 45-byte

address (ASCII), and another 4 bytes for the person's telephone number (an unsigned

long). This list then has four elements, which we can label LO, LI, L2, and L3, and