Page 51 - Introduction to Mineral Exploration

P. 51

34 A.M. EVANS & C.J. MOON

Flat Thick impervious shale

Limestone

Strike of orebody

D B

Shale

Pitch or

A Dip rake Limestone

Shale

Plunge

E Sandstone

Hanging Footwall

wall

AB and CB lie in the same 20 m

Axis of orebody DB, AB and EB are in the

vertical plane.

same horizontal plane and

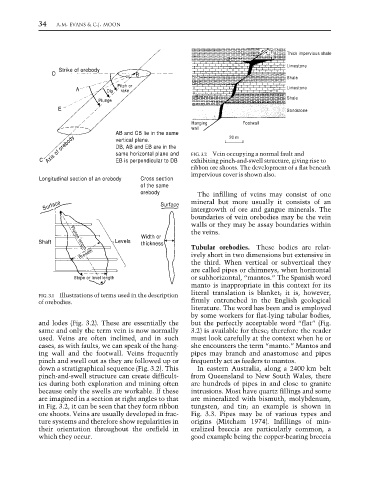

C EB is perpendicular to DB FIG. 3.2 Vein occupying a normal fault and

exhibiting pinch-and-swell structure, giving rise to

ribbon ore shoots. The development of a flat beneath

impervious cover is shown also.

Longitudinal section of an orebody Cross section

of the same

orebody The infilling of veins may consist of one

Surface Surface mineral but more usually it consists of an

intergrowth of ore and gangue minerals. The

boundaries of vein orebodies may be the vein

walls or they may be assay boundaries within

the veins.

Width or

Shaft Levels thickness Tubular orebodies. These bodies are relat-

Plunge length

Breadth ively short in two dimensions but extensive in

the third. When vertical or subvertical they

are called pipes or chimneys, when horizontal

Stope or level length or subhorizontal, “mantos.” The Spanish word

manto is inappropriate in this context for its

FIG. 3.1 Illustrations of terms used in the description literal translation is blanket; it is, however,

of orebodies. firmly entrenched in the English geological

literature. The word has been and is employed

by some workers for flat-lying tabular bodies,

and lodes (Fig. 3.2). These are essentially the but the perfectly acceptable word “flat” (Fig.

same and only the term vein is now normally 3.2) is available for these; therefore the reader

used. Veins are often inclined, and in such must look carefully at the context when he or

cases, as with faults, we can speak of the hang- she encounters the term “manto.” Mantos and

ing wall and the footwall. Veins frequently pipes may branch and anastomose and pipes

pinch and swell out as they are followed up or frequently act as feeders to mantos.

down a stratigraphical sequence (Fig. 3.2). This In eastern Australia, along a 2400 km belt

pinch-and-swell structure can create difficult- from Queensland to New South Wales, there

ies during both exploration and mining often are hundreds of pipes in and close to granite

because only the swells are workable. If these intrusions. Most have quartz fillings and some

are imagined in a section at right angles to that are mineralized with bismuth, molybdenum,

in Fig. 3.2, it can be seen that they form ribbon tungsten, and tin; an example is shown in

ore shoots. Veins are usually developed in frac- Fig. 3.3. Pipes may be of various types and

ture systems and therefore show regularities in origins (Mitcham 1974). Infillings of min-

their orientation throughout the orefield in eralized breccia are particularly common, a

which they occur. good example being the copper-bearing breccia