Page 160 - Introduction to Paleobiology and The Fossil Record

P. 160

FOSSIL FORM AND FUNCTION 147

Late

Scaphonyx

(A)

(J)

ontogeny

Rhynchosaurus

Triassic Mid (A)

peramorphocline

Stenaulorhynchus

(A)

Early Mesosuchus (?A) 50 mm

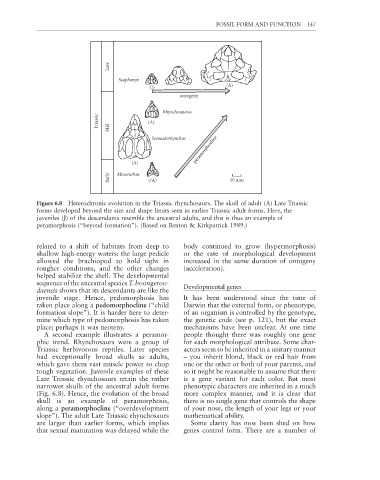

Figure 6.8 Heterochronic evolution in the Triassic rhynchosaurs. The skull of adult (A) Late Triassic

forms developed beyond the size and shape limits seen in earlier Triassic adult forms. Here, the

juveniles (J) of the descendants resemble the ancestral adults, and this is thus an example of

peramorphosis (“beyond formation”). (Based on Benton & Kirkpatrick 1989.)

related to a shift of habitats from deep to body continued to grow (hypermorphosis)

shallow high-energy waters: the large pedicle or the rate of morphological development

allowed the brachiopod to hold tight in increased in the same duration of ontogeny

rougher conditions, and the other changes (acceleration).

helped stabilize the shell. The developmental

sequence of the ancestral species T. boongeroo-

daensis shows that its descendants are like the Developmental genes

juvenile stage. Hence, pedomorphosis has It has been understood since the time of

taken place along a pedomorphocline (“child Darwin that the external form, or phenotype,

formation slope”). It is harder here to deter- of an organism is controlled by the genotype,

mine which type of pedomorphosis has taken the genetic code (see p. 121), but the exact

place; perhaps it was neoteny. mechanisms have been unclear. At one time

A second example illustrates a peramor- people thought there was roughly one gene

phic trend. Rhynchosaurs were a group of for each morphological attribute. Some char-

Triassic herbivorous reptiles. Later species acters seem to be inherited in a unitary manner

had exceptionally broad skulls as adults, – you inherit blond, black or red hair from

which gave them vast muscle power to chop one or the other or both of your parents, and

tough vegetation. Juvenile examples of these so it might be reasonable to assume that there

Late Triassic rhynchosaurs retain the rather is a gene variant for each color. But most

narrower skulls of the ancestral adult forms phenotypic characters are inherited in a much

(Fig. 6.8). Hence, the evolution of the broad more complex manner, and it is clear that

skull is an example of peramorphosis, there is no single gene that controls the shape

along a peramorphocline (“overdevelopment of your nose, the length of your legs or your

slope”). The adult Late Triassic rhynchosaurs mathematical ability.

are larger than earlier forms, which implies Some clarity has now been shed on how

that sexual maturation was delayed while the genes control form. There are a number of