Page 118 - Petroleum Geology

P. 118

96

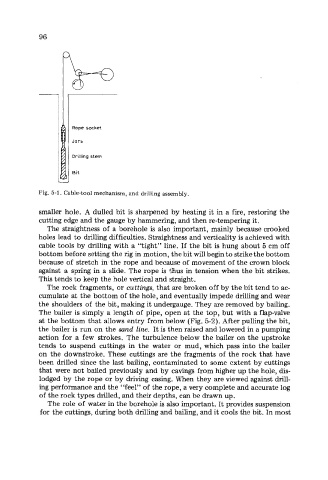

Rope socket

Jars

Drilling stem

Bit

Fig. 5-1. Cable-tool mechanism, and drilling assembly.

smaller hole. A dulled bit is sharpened by heating it in a fire, restoring the

cutting edge and the gauge by hammering, and then re-tempering it.

The straightness of a borehole is also important, mainly because crooked

holes lead to drilling difficulties. Straightness and verticality is achieved with

cable tools by drilling with a “tight” line. If the bit is hung about 5 cm off

bottom before setting the rig in motion, the bit will begin to strike the bottom

because of stretch in the rope and because of movement of the crown block

against a spring in a slide. The rope is 9ius in tension when the bit strikes.

This tends to keep the hole vertical and straight.

The rock fragments, or cuttings, that are broken off by the bit tend to ac-

cumulate at the bottom of the hole, and eventually impede drilling and wear

the shoulders of the bit, making it undergauge. They are removed by bailing.

The bailer is simply a length of pipe, open at the top, but with a flap-valve

at the bottom that allows entry from below (Fig. 5-2). After pulling the bit,

the bailer is run on the sand line. It is then raised and lowered in a pumping

action for a few strokes. The turbulence below the bailer on the upstroke

tends to suspend cuttings in the water or mud, which pass into the bailer

on the downstroke. These cuttings are the fragments of the rock that have

been drilled since the last bailing, contaminated to some extent by cuttings

that were not bailed previously and by cavings from higher up the hole, dis-

lodged by the rope or by driving casing. When they are viewed against drill-

ing performance and the “feel” of the rope, a very complete and accurate log

of the rock types drilled, and their depths, can be drawn up.

The role of water in the borehole is also important. It provides suspension

for the cuttings, during both drilling and bailing, and it cools the bit. In most