Page 225 - Petroleum Geology

P. 225

202

oillwater contacts on the two flanks of some oil fields differ by as muchas

150 m.

The effective drainage areas of wells in carbonate reservoirs with fracture

porosity are large, and productivity of wells is usually large. These are impor-

tant factors in the economics of oil production because the oil can be produced

with relatively few wells. High productivity is one of the characteristics of

carbonate reservoirs, including reef reservoirs. Intisar field, Libya, for example,

tested one well at 74,867 bbl/day (11,900 m3/day) clean 37' API oil (sp.

gr., 0.84) from 223 m (731 ft) of fossil reef (World Oil, January 1968).

As regards irreducible water saturations, less is known of carbonate reser-

voirs than of sandstone reservoirs, and some carbonate reservoirs are thought

to be oil-wet. It seems certain, however, that oil and gas will come into close

contact with solid carbonate surfaces in the reservoir. In reservoirs with frac-

ture porosity, the irreducible water saturation is probably very low in the

fractures, but may be high in the rock itself.

Of particular importance in carbonate provinces is the evidence for differ-

ential entrapment of oil and gas. GUSSOW'S (1954) hypothesis of differential

entrapment is very simple, and it grew from the observation that in a sequence

of reefs in a single trend in the Western Canada basin, the deepest reefs con-

tain gas only; the shallowest, water only; there will be one deep reef with a

gas/oil contact, and one shallow one with an oil/water contact, but the others

will be full to spill point. Gussow explained this characteristic distribution as

follows:

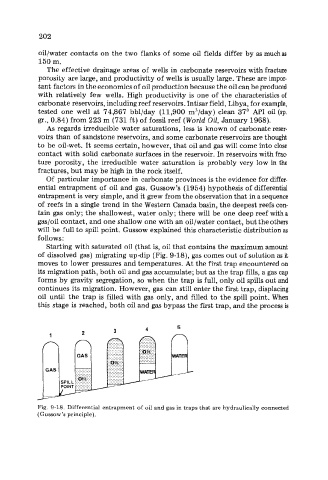

Starting with saturated oil (that is, oil that contains the maximum amount

of dissolved gas) migrating updip (Fig. 9-18), gas comes out of solution as it

moves to lower pressures and temperatures. At the first trap encountered on

its migration path, both oil and gas accumulate; but as the trap fills, a gas cap

forms by gravity segregation, so when the trap is full, only oil spills out and

continues its migration. However, gas can still enter the first trap, displacing

oil until the trap is filled with gas only, and filled to the spill point. When

this stage is reached, both oil and gas bypass the first trap, and the process is

Fig. 9-18, Differential entrapment of oil and gas in traps that are hydraulically connected

(Gussow's principle).