Page 22 - Physical Chemistry

P. 22

lev38627_ch01.qxd 2/20/08 11:38 AM Page 3

3

radius 2.5 nm melt at 930 K, and catalyze many reactions; gold nanoparticles of 100 nm Section 1.2

radius are purple-pink, of 20 nm radius are red, and of 1 nm radius are orange; gold Thermodynamics

particles of 1 nm or smaller radius are electrical insulators. The term mesoscopic is

sometimes used to refer to systems larger than nanoscopic but smaller than macro-

scopic. Thus we have the progressively larger size levels: atomic → nanoscopic →

mesoscopic → macroscopic.

1.2 THERMODYNAMICS

Thermodynamics

We begin our study of physical chemistry with thermodynamics. Thermodynamics

(from the Greek words for “heat” and “power”) is the study of heat, work, energy, and

the changes they produce in the states of systems. In a broader sense, thermodynamics

studies the relationships between the macroscopic properties of a system. A key prop-

erty in thermodynamics is temperature, and thermodynamics is sometimes defined as

the study of the relation of temperature to the macroscopic properties of matter.

We shall be studying equilibrium thermodynamics, which deals with systems in

equilibrium. (Irreversible thermodynamics deals with nonequilibrium systems and

rate processes.) Equilibrium thermodynamics is a macroscopic science and is inde-

pendent of any theories of molecular structure. Strictly speaking, the word “molecule”

is not part of the vocabulary of thermodynamics. However, we won’t adopt a purist

attitude but will often use molecular concepts to help us understand thermodynamics.

Thermodynamics does not apply to systems that contain only a few molecules; a sys-

tem must contain a great many molecules for it to be treated thermodynamically. The

term “thermodynamics” in this book will always mean equilibrium thermodynamics.

Thermodynamic Systems

The macroscopic part of the universe under study in thermodynamics is called the

system. The parts of the universe that can interact with the system are called the

surroundings.

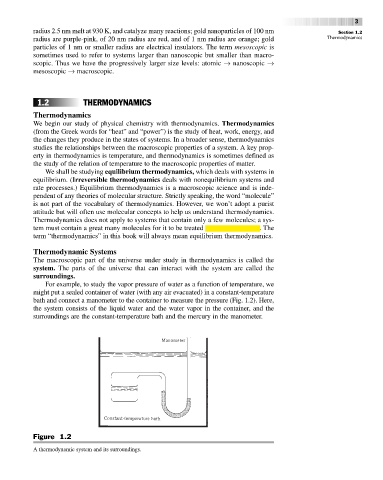

Forexample, to study the vapor pressure of water as a function of temperature, we

might put a sealed container of water (with any air evacuated) in a constant-temperature

bath and connect a manometer to the container to measure the pressure (Fig. 1.2). Here,

the system consists of the liquid water and the water vapor in the container, and the

surroundings are the constant-temperature bath and the mercury in the manometer.

Figure 1.2

A thermodynamic system and its surroundings.