Page 179 - The Art of Designing Embedded Systems

P. 179

166 THE ART OF DESIGNING EMBEDDED SYSTEMS

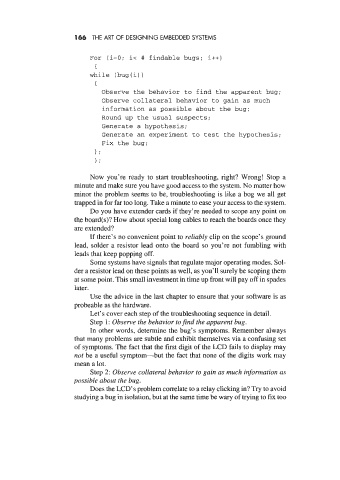

For (i=O; i< # findable bugs; i++)

{

while (bug(i)

)

I

Observe the behavior to find the apparent bug;

Observe collateral behavior to gain as much

information as possible about the bug;

Round up the usual suspects;

Generate a hypothesis;

Generate an experiment to test the hypothesis;

Fix the bug;

I;

1;

Now you’re ready to start troubleshooting, right? Wrong! Stop a

minute and make sure you have good access to the system. No matter how

minor the problem seems to be, troubleshooting is like a bog we all get

trapped in for far too long. Take a minute to ease your access to the system.

Do you have extender cards if they’re needed to scope any point on

the board(s)? How about special long cables to reach the boards once they

are extended?

If there’s no convenient point to reliably clip on the scope’s ground

lead, solder a resistor lead onto the board so you’re not fumbling with

leads that keep popping off.

Some systems have signals that regulate major operating modes. Sol-

der a resistor lead on these points as well, as you’ll surely be scoping them

at some point. This small investment in time up front will pay off in spades

later.

Use the advice in the last chapter to ensure that your software is as

probeable as the hardware.

Let’s cover each step of the troubleshooting sequence in detail.

Step 1: Observe the behavior tofind the apparent bug.

In other words, determine the bug’s symptoms. Remember always

that many problems are subtle and exhibit themselves via a confusing set

of symptoms. The fact that the first digit of the LCD fails to display may

not be a useful symptom-but the fact that none of the digits work may

mean a lot.

Step 2: Observe collateral behavior to gain as much information as

possible about the bug.

Does the LCD’s problem correlate to a relay clicking in? Try to avoid

studying a bug in isolation, but at the same time be wary of trying to fix too