Page 506 - Bruce Ellig - The Complete Guide to Executive Compensation (2007)

P. 506

492 The Complete Guide to Executive Compensation

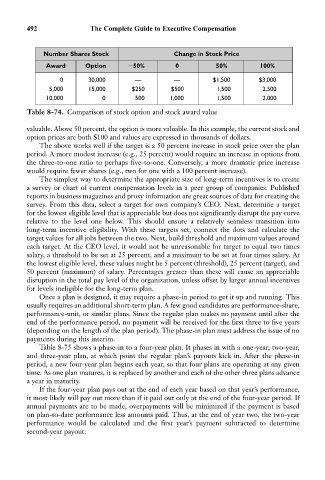

Number Shares Stock Change in Stock Price

Award Option 50% 0 50% 100%

0 30,000 — — $1,500 $3,000

5,000 15,000 $250 $500 1,500 2,500

10,000 0 500 1,000 1,500 2,000

Table 8-74. Comparison of stock option and stock award value

valuable. Above 50 percent, the option is more valuable. In this example, the current stock and

option prices are both $100 and values are expressed in thousands of dollars.

The above works well if the target is a 50 percent increase in stock price over the plan

period. A more modest increase (e.g., 25 percent) would require an increase in options from

the three-to-one ratio to perhaps five-to-one. Conversely, a more dramatic price increase

would require fewer shares (e.g., two for one with a 100 percent increase).

The simplest way to determine the appropriate size of long-term incentives is to create

a survey or chart of current compensation levels in a peer group of companies. Published

reports in business magazines and proxy information are great sources of data for creating the

survey. From this data, select a target for own company’s CEO. Next, determine a target

for the lowest eligible level that is appreciable but does not significantly disrupt the pay curve

relative to the level one below. This should ensure a relatively seamless transition into

long-term incentive eligibility. With these targets set, connect the dots and calculate the

target values for all jobs between the two. Next, build threshold and maximum values around

each target. At the CEO level, it would not be unreasonable for target to equal two times

salary, a threshold to be set at 25 percent, and a maximum to be set at four times salary. At

the lowest eligible level, these values might be 5 percent (threshold), 25 percent (target), and

50 percent (maximum) of salary. Percentages greater than these will cause an appreciable

disruption in the total pay level of the organization, unless offset by larger annual incentives

for levels ineligible for the long-term plan.

Once a plan is designed, it may require a phase-in period to get it up and running. This

usually requires an additional short-term plan. A few good candidates are performance-share,

performance-unit, or similar plans. Since the regular plan makes no payment until after the

end of the performance period, no payment will be received for the first three to five years

(depending on the length of the plan period). The phase-in plan must address the issue of no

payments during this interim.

Table 8-75 shows a phase-in to a four-year plan. It phases in with a one-year, two-year,

and three-year plan, at which point the regular plan’s payouts kick in. After the phase-in

period, a new four-year plan begins each year, so that four plans are operating at any given

time. As one plan matures, it is replaced by another and each of the other three plans advance

a year in maturity.

If the four-year plan pays out at the end of each year based on that year’s performance,

it most likely will pay out more than if it paid out only at the end of the four-year period. If

annual payments are to be made, overpayments will be minimized if the payment is based

on plan-to-date performance less amounts paid. Thus, at the end of year two, the two-year

performance would be calculated and the first year’s payment subtracted to determine

second-year payout.