Page 54 - The Resilient Organization

P. 54

Parts More Resilient than the Whole 41

Part of the reason for this dark prediction is that the absence of a sur-

prise or a catastrophe (which might indicate luck or good resilience) tends

to increase temptation for discounting the probability of an event like that

happening, and hence reducing (costly) preparation measures. Thus the bet-

ter job we do in resilience, the less we are willing to invest in it (paradoxi-

cally, something that is working marvelously).

It is difficult in our minds to differentiate between the frequency of an

event and its probability: something not having happened in the past makes

us trust that it won’t happen in the future either. We should not trust this

probability calculator of ours. Our past experience (of event frequency) is a

poor guide for future probabilities.

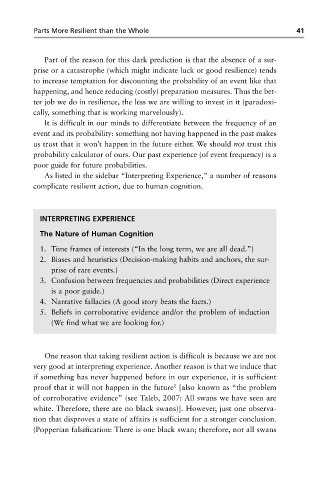

As listed in the sidebar “Interpreting Experience,” a number of reasons

complicate resilient action, due to human cognition.

INTERPRETING EXPERIENCE

The Nature of Human Cognition

1. Time frames of interests (“In the long term, we are all dead.”)

2. Biases and heuristics (Decision-making habits and anchors, the sur-

prise of rare events.)

3. Confusion between frequencies and probabilities (Direct experience

is a poor guide.)

4. Narrative fallacies (A good story beats the facts.)

5. Beliefs in corroborative evidence and/or the problem of induction

(We find what we are looking for.)

One reason that taking resilient action is difficult is because we are not

very good at interpreting experience. Another reason is that we induce that

if something has never happened before in our experience, it is sufficient

1

proof that it will not happen in the future [also known as “the problem

of corroborative evidence” (see Taleb, 2007: All swans we have seen are

white. Therefore, there are no black swans)]. However, just one observa-

tion that disproves a state of affairs is sufficient for a stronger conclusion.

(Popperian falsification: There is one black swan; therefore, not all swans