Page 175 - Visions of the Future Chemistry and Life Science

P. 175

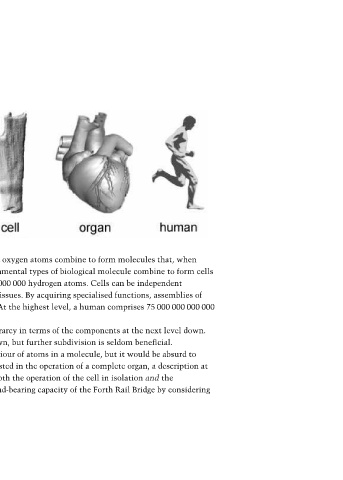

Figure 9.2. The biological hierarchy. Assemblies of carbon, hydrogen and oxygen atoms combine to form molecules that, when

linked together, form proteins, carbohydrates and fats. These three fundamental types of biological molecule combine to form cells

that are typically 0.01 mm in diameter and have the mass of 30 000 000 000 000 hydrogen atoms. Cells can be independent

organisms, as in a bacterium, or, by co-operating with other cells, form tissues. By acquiring specialised functions, assemblies of

tissues form the next distinct structural and functional unit, the organ. At the highest level, a human comprises 75 000 000 000 000

cells divided into ten major organ systems.

It is natural to describe the function at each level in the biological hierarcy in terms of the components at the next level down.

Sometimes it is necessary to consider processes occurring two levels down, but further subdivision is seldom beneficial.

Schrödinger’s equation, for example, is useful when modelling the behaviour of atoms in a molecule, but it would be absurd to

model car crashworthiness using this level of detail. When we are interested in the operation of a complete organ, a description at

the level of the cell is the natural choice. The model must incorporate both the operation of the cell in isolation and the

interactions between cells since, by analogy, we could not predict the load-bearing capacity of the Forth Rail Bridge by considering

only the strength of the individual cantilevers in isolation.