Page 293 - Fundamentals of Ocean Renewable Energy Generating Electricity From The Sea

P. 293

280 Fundamentals of Ocean Renewable Energy

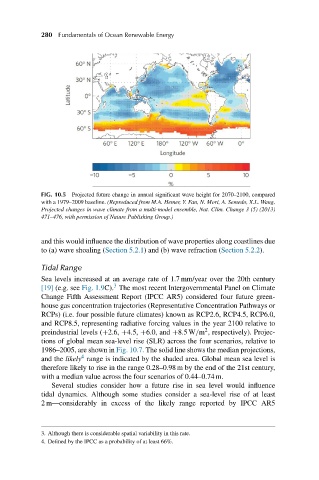

FIG. 10.5 Projected future change in annual significant wave height for 2070–2100, compared

with a 1979–2009 baseline. (Reproduced from M.A. Hemer, Y. Fan, N. Mori, A. Semedo, X.L. Wang,

Projected changes in wave climate from a multi-model ensemble, Nat. Clim. Change 3 (5) (2013)

471–476, with permission of Nature Publishing Group.)

and this would influence the distribution of wave properties along coastlines due

to (a) wave shoaling (Section 5.2.1) and (b) wave refraction (Section 5.2.2).

Tidal Range

Sea levels increased at an average rate of 1.7 mm/year over the 20th century

3

[19] (e.g. see Fig. 1.9C). The most recent Intergovernmental Panel on Climate

Change Fifth Assessment Report (IPCC AR5) considered four future green-

house gas concentration trajectories (Representative Concentration Pathways or

RCPs) (i.e. four possible future climates) known as RCP2.6, RCP4.5, RCP6.0,

and RCP8.5, representing radiative forcing values in the year 2100 relative to

2

preindustrial levels (+2.6, +4.5, +6.0, and +8.5 W/m , respectively). Projec-

tions of global mean sea-level rise (SLR) across the four scenarios, relative to

1986–2005, are shown in Fig. 10.7. The solid line shows the median projections,

4

and the likely range is indicated by the shaded area. Global mean sea level is

therefore likely to rise in the range 0.28–0.98 m by the end of the 21st century,

with a median value across the four scenarios of 0.44–0.74 m.

Several studies consider how a future rise in sea level would influence

tidal dynamics. Although some studies consider a sea-level rise of at least

2 m—considerably in excess of the likely range reported by IPCC AR5

3. Although there is considerable spatial variability in this rate.

4. Defined by the IPCC as a probability of at least 66%.