Page 149 - gas transport in porous media

P. 149

142

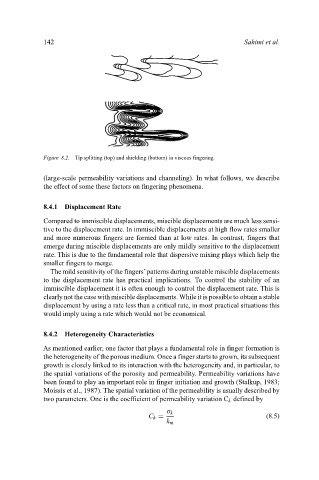

Figure 8.2. Tip splitting (top) and shielding (bottom) in viscous fingering Sahimi et al.

(large-scale permeability variations and channeling). In what follows, we describe

the effect of some these factors on fingering phenomena.

8.4.1 Displacement Rate

Compared to immiscible displacements, miscible displacements are much less sensi-

tive to the displacement rate. In immiscible displacements at high flow rates smaller

and more numerous fingers are formed than at low rates. In contrast, fingers that

emerge during miscible displacements are only mildly sensitive to the displacement

rate. This is due to the fundamental role that dispersive mixing plays which help the

smaller fingers to merge.

The mild sensitivity of the fingers’patterns during unstable miscible displacements

to the displacement rate has practical implications. To control the stability of an

immiscible displacement it is often enough to control the displacement rate. This is

clearly not the case with miscible displacements. While it is possible to obtain a stable

displacement by using a rate less than a critical rate, in most practical situations this

would imply using a rate which would not be economical.

8.4.2 Heterogeneity Characteristics

As mentioned earlier, one factor that plays a fundamental role in finger formation is

the heterogeneity of the porous medium. Once a finger starts to grown, its subsequent

growth is closely linked to its interaction with the heterogeneity and, in particular, to

the spatial variations of the porosity and permeability. Permeability variations have

been found to play an important role in finger initiation and growth (Stalkup, 1983;

Moissis et al., 1987). The spatial variation of the permeability is usually described by

two parameters. One is the coefficient of permeability variation C k defined by

σ k

C k = (8.5)

k m