Page 545 - Handbooks of Applied Linguistics Communication Competence Language and Communication Problems Practical Solutions

P. 545

Adapting authentic workplace talk for workplace training 523

Gumperz in this volume). It is essential that study of the sociopragmatic features

of an authentic interaction takes these factors into account, although such explo-

ration may be somewhat speculative given the limited availability of this kind of

information. Let me use example (1) to illustrate this point.

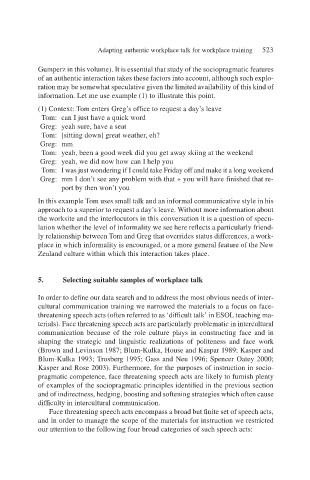

(1) Context: Tom enters Greg’s office to request a day’s leave

Tom: can I just have a quick word

Greg: yeah sure, have a seat

Tom: [sitting down] great weather, eh?

Greg: mm

Tom: yeah, been a good week did you get away skiing at the weekend

Greg: yeah, we did now how can I help you

Tom: I was just wondering if I could take Friday off and make it a long weekend

Greg: mm I don’t see any problem with that + you will have finished that re-

port by then won’t you

In this example Tom uses small talk and an informal communicative style in his

approach to a superior to request a day’s leave. Without more information about

the worksite and the interlocutors in this conversation it is a question of specu-

lation whether the level of informality we see here reflects a particularly friend-

ly relationship between Tom and Greg that overrides status differences, a work-

place in which informality is encouraged, or a more general feature of the New

Zealand culture within which this interaction takes place.

5. Selecting suitable samples of workplace talk

In order to define our data search and to address the most obvious needs of inter-

cultural communication training we narrowed the materials to a focus on face-

threatening speech acts (often referred to as ‘difficult talk’ in ESOL teaching ma-

terials). Face threatening speech acts are particularly problematic in intercultural

communication because of the role culture plays in constructing face and in

shaping the strategic and linguistic realizations of politeness and face work

(Brown and Levinson 1987; Blum-Kulka, House and Kaspar 1989; Kasper and

Blum-Kulka 1993; Trosberg 1995; Gass and Neu 1996; Spencer Oatey 2000;

Kasper and Rose 2003). Furthermore, for the purposes of instruction in socio-

pragmatic competence, face threatening speech acts are likely to furnish plenty

of examples of the sociopragmatic principles identified in the previous section

and of indirectness, hedging, boosting and softening strategies which often cause

difficulty in intercultural communication.

Face threatening speech acts encompass a broad but finite set of speech acts,

and in order to manage the scope of the materials for instruction we restricted

our attention to the following four broad categories of such speech acts: