Page 299 - Hydrogeology Principles and Practice

P. 299

HYDC08 12/5/05 5:31 PM Page 282

282 Chapter Eight

from beneath the Libyan desert and its transfer to

coastal cities and towns. Clearly the groundwater

supply is not a permanent, renewable resource but

for a period of at least decades this fossil water can

supply most of the population of Libya with an essen-

tial resource. As argued by Price (2002), the GMRP

appears to meet the ethical requirements of ground-

water mining, namely that: (i) evidence is available

that pumping can be maintained for a long period;

(ii) the negative impacts of development are smaller

than the benefits; and (iii) the users and decision-

makers are aware that the resource will be eventually

depleted. However, Price (2002) is concerned that

using non-renewable groundwater for inefficient

agriculture in a region where there is effectively no

recharge is not a sensible long-term plan.

8.2.3 Regional-scale groundwater

development schemes

The above two examples of large-scale groundwater

developments in support of irrigated agriculture tip

the sustainability equation towards economic gain.

At the regional scale, effective river basin management

can develop the large storage volume in aquifers in

conjunction with surface resources. This concept is

not new and several schemes, principally the Thames,

Great Ouse, Severn, Itchen and Waveney Schemes,

were developed in England and Wales following

the Water Resources Act of 1963 (see Section 1.7).

Pilot studies were undertaken to assess the feasibility

of regulating rivers by pumping groundwater into

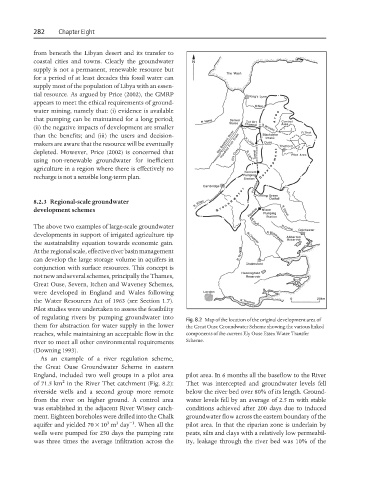

Fig. 8.2 Map of the location of the original development area of

them for abstraction for water supply in the lower the Great Ouse Groundwater Scheme showing the various linked

reaches, while maintaining an acceptable flow in the components of the current Ely Ouse Essex Water Transfer

river to meet all other environmental requirements Scheme.

(Downing 1993).

As an example of a river regulation scheme,

the Great Ouse Groundwater Scheme in eastern

England, included two well groups in a pilot area pilot area. In 6 months all the baseflow to the River

2

of 71.5 km in the River Thet catchment (Fig. 8.2): Thet was intercepted and groundwater levels fell

riverside wells and a second group more remote below the river bed over 80% of its length. Ground-

from the river on higher ground. A control area water levels fell by an average of 2.5 m with stable

was established in the adjacent River Wissey catch- conditions achieved after 200 days due to induced

ment. Eighteen boreholes were drilled into the Chalk groundwater flow across the eastern boundary of the

3

−1

3

aquifer and yielded 70 × 10 m day . When all the pilot area. In that the riparian zone is underlain by

wells were pumped for 250 days the pumping rate peats, silts and clays with a relatively low permeabil-

was three times the average infiltration across the ity, leakage through the river bed was 10% of the