Page 229 - Information and American Democracy Technology in the Evolution of Political Power

P. 229

P1: IBE/IRP/IQR/IRR

CY101-Bimber

August 13, 2002

CY101-05

0 521 80067 6

Political Individuals 12:12

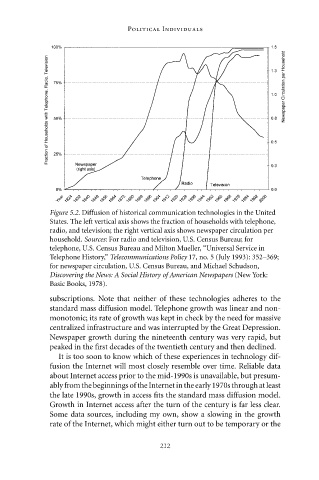

Figure 5.2. Diffusion of historical communication technologies in the United

States. The left vertical axis shows the fraction of households with telephone,

radio, and television; the right vertical axis shows newspaper circulation per

household. Sources: For radio and television, U.S. Census Bureau; for

telephone, U.S. Census Bureau and Milton Mueller, “Universal Service in

Telephone History,” Telecommunications Policy 17, no. 5 (July 1993): 352–369;

for newspaper circulation, U.S. Census Bureau, and Michael Schudson,

Discovering the News: A Social History of American Newspapers (New York:

Basic Books, 1978).

subscriptions. Note that neither of these technologies adheres to the

standard mass diffusion model. Telephone growth was linear and non-

monotonic; its rate of growth was kept in check by the need for massive

centralized infrastructure and was interrupted by the Great Depression.

Newspaper growth during the nineteenth century was very rapid, but

peaked in the first decades of the twentieth century and then declined.

It is too soon to know which of these experiences in technology dif-

fusion the Internet will most closely resemble over time. Reliable data

about Internet access prior to the mid-1990s is unavailable, but presum-

ablyfromthebeginningsoftheInternetintheearly1970sthroughatleast

the late 1990s, growth in access fits the standard mass diffusion model.

Growth in Internet access after the turn of the century is far less clear.

Some data sources, including my own, show a slowing in the growth

rate of the Internet, which might either turn out to be temporary or the

212