Page 145 - Introduction to Mineral Exploration

P. 145

128 J. MILSOM

nT require physical contact with the ground and

Total field can therefore be made from aircraft. Inevitably,

(a) direction

100 there is some loss of sensitivity, since detectors

are further from sources, but this may even

be useful in filtering out local effects from

manmade objects. The main virtue of airborne

work is, however, the speed with which large

Magnetic areas can be covered. Surveys may be flown

either at a constant altitude or (more com-

monly in mineral exploration) at a (nominally)

g.u.

constant height above the ground. Aircraft

(b) 10 are often fitted with multiple sensors and

most installations include a magnetometer

(Fig. 7.2).

5

Airborne surveys require good navigational

control, both at the time of survey and later,

when flight paths have to be plotted (recov-

Gravity ered). Traditionally, the pilot was guided by a

% navigator equipped with maps or photo-mosaics

(c) 5 showing the planned line locations. Course

changes were avoided unless absolutely neces-

sary and in many cases the navigator’s main job

Electromagnetic was to ensure that each line was at least begun

−5 (CWEM) in the right place. Although infills were (and

are) required if lines diverged too much, a line

that was slightly out of position was preferred

to one that continually changed direction and

% was therefore difficult to plot accurately.

Low level navigation is not easy, since even

(d) 5 the best landmarks may be visible for only a

few seconds when flying a few hundred meters

above the ground, and navigators’ opinions of

Electromagnetic where they had been would have been very in-

(VLF)

adequate bases for geophysical maps. Tracking

−5

cameras were therefore used to record images,

either continuously or as overlapping frames,

on 35 mm film. Because of the generally small

terrain clearance, very wide-angle (“fish-eye”)

lenses were used to give broad, although dis-

torted, fields of view. Recovery was done dir-

ectly from the negatives and even the most

experienced plotters were likely to misidentify

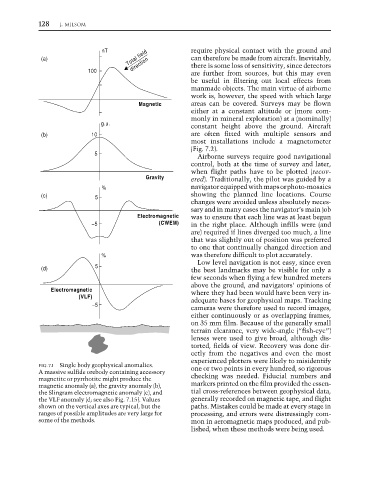

FIG. 7.1 Single body geophysical anomalies. one or two points in every hundred, so rigorous

A massive sulfide orebody containing accessory

magnetite or pyrrhotite might produce the checking was needed. Fiducial numbers and

magnetic anomaly (a), the gravity anomaly (b), markers printed on the film provided the essen-

the Slingram electromagnetic anomaly (c), and tial cross-references between geophysical data,

the VLF anomaly (d; see also Fig. 7.15). Values generally recorded on magnetic tape, and flight

shown on the vertical axes are typical, but the paths. Mistakes could be made at every stage in

ranges of possible amplitudes are very large for processing, and errors were distressingly com-

some of the methods. mon in aeromagnetic maps produced, and pub-

lished, when these methods were being used.