Page 81 - Master Handbook of Acoustics

P. 81

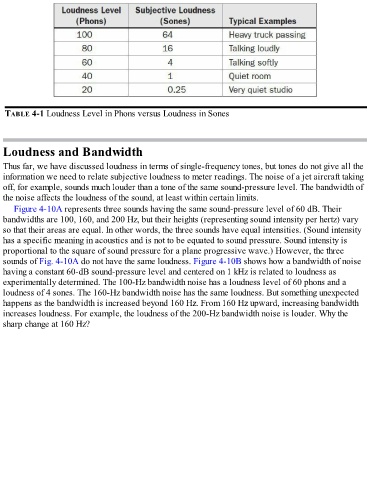

TABLE 4-1 Loudness Level in Phons versus Loudness in Sones

Loudness and Bandwidth

Thus far, we have discussed loudness in terms of single-frequency tones, but tones do not give all the

information we need to relate subjective loudness to meter readings. The noise of a jet aircraft taking

off, for example, sounds much louder than a tone of the same sound-pressure level. The bandwidth of

the noise affects the loudness of the sound, at least within certain limits.

Figure 4-10A represents three sounds having the same sound-pressure level of 60 dB. Their

bandwidths are 100, 160, and 200 Hz, but their heights (representing sound intensity per hertz) vary

so that their areas are equal. In other words, the three sounds have equal intensities. (Sound intensity

has a specific meaning in acoustics and is not to be equated to sound pressure. Sound intensity is

proportional to the square of sound pressure for a plane progressive wave.) However, the three

sounds of Fig. 4-10A do not have the same loudness. Figure 4-10B shows how a bandwidth of noise

having a constant 60-dB sound-pressure level and centered on 1 kHz is related to loudness as

experimentally determined. The 100-Hz bandwidth noise has a loudness level of 60 phons and a

loudness of 4 sones. The 160-Hz bandwidth noise has the same loudness. But something unexpected

happens as the bandwidth is increased beyond 160 Hz. From 160 Hz upward, increasing bandwidth

increases loudness. For example, the loudness of the 200-Hz bandwidth noise is louder. Why the

sharp change at 160 Hz?