Page 175 - Modern Optical Engineering The Design of Optical Systems

P. 175

158 Chapter Eight

(or more exactly, 39.37 D). For a single surface, the dioptric power

is given by (n′ n)/R, with R the radius in meters. A 1-diopter

prism produces a deviation of 1 cm in a 1-m distance, i.e., a deviation

of 0.01 radians, or about 0.57 degrees.

8.2 The Structure of the Eye

The eyeball is a tough plasticlike shell filled largely with a jellylike

substance under sufficient pressure to maintain its shape. It rides in

a bony socket of the skull on pads of flesh and fat. It is held in place

and rotated by six muscles.

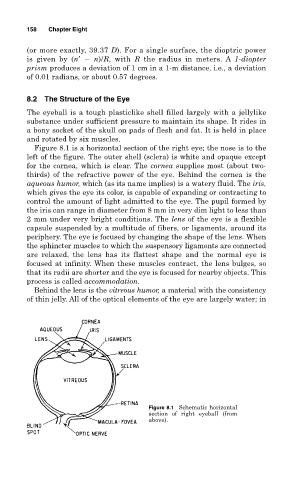

Figure 8.1 is a horizontal section of the right eye; the nose is to the

left of the figure. The outer shell (sclera) is white and opaque except

for the cornea, which is clear. The cornea supplies most (about two-

thirds) of the refractive power of the eye. Behind the cornea is the

aqueous humor, which (as its name implies) is a watery fluid. The iris,

which gives the eye its color, is capable of expanding or contracting to

control the amount of light admitted to the eye. The pupil formed by

the iris can range in diameter from 8 mm in very dim light to less than

2 mm under very bright conditions. The lens of the eye is a flexible

capsule suspended by a multitude of fibers, or ligaments, around its

periphery. The eye is focused by changing the shape of the lens. When

the sphincter muscles to which the suspensory ligaments are connected

are relaxed, the lens has its flattest shape and the normal eye is

focused at infinity. When these muscles contract, the lens bulges, so

that its radii are shorter and the eye is focused for nearby objects. This

process is called accommodation.

Behind the lens is the vitreous humor, a material with the consistency

of thin jelly. All of the optical elements of the eye are largely water; in

Figure 8.1 Schematic horizontal

section of right eyeball (from

above).