Page 55 -

P. 55

CHAPTER 1 • THE NATURE OF STRATEGIC MANAGEMENT 21

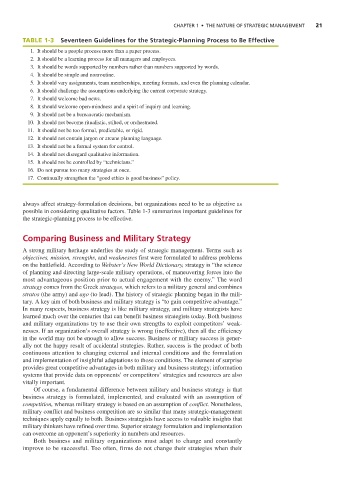

TABLE 1-3 Seventeen Guidelines for the Strategic-Planning Process to Be Effective

1. It should be a people process more than a paper process.

2. It should be a learning process for all managers and employees.

3. It should be words supported by numbers rather than numbers supported by words.

4. It should be simple and nonroutine.

5. It should vary assignments, team memberships, meeting formats, and even the planning calendar.

6. It should challenge the assumptions underlying the current corporate strategy.

7. It should welcome bad news.

8. It should welcome open-mindness and a spirit of inquiry and learning.

9. It should not be a bureaucratic mechanism.

10. It should not become ritualistic, stilted, or orchestrated.

11. It should not be too formal, predictable, or rigid.

12. It should not contain jargon or arcane planning language.

13. It should not be a formal system for control.

14. It should not disregard qualitative information.

15. It should not be controlled by “technicians.”

16. Do not pursue too many strategies at once.

17. Continually strengthen the “good ethics is good business” policy.

always affect strategy-formulation decisions, but organizations need to be as objective as

possible in considering qualitative factors. Table 1-3 summarizes important guidelines for

the strategic-planning process to be effective.

Comparing Business and Military Strategy

A strong military heritage underlies the study of strategic management. Terms such as

objectives, mission, strengths, and weaknesses first were formulated to address problems

on the battlefield. According to Webster’s New World Dictionary, strategy is “the science

of planning and directing large-scale military operations, of maneuvering forces into the

most advantageous position prior to actual engagement with the enemy.” The word

strategy comes from the Greek strategos, which refers to a military general and combines

stratos (the army) and ago (to lead). The history of strategic planning began in the mili-

tary. A key aim of both business and military strategy is “to gain competitive advantage.”

In many respects, business strategy is like military strategy, and military strategists have

learned much over the centuries that can benefit business strategists today. Both business

and military organizations try to use their own strengths to exploit competitors’ weak-

nesses. If an organization’s overall strategy is wrong (ineffective), then all the efficiency

in the world may not be enough to allow success. Business or military success is gener-

ally not the happy result of accidental strategies. Rather, success is the product of both

continuous attention to changing external and internal conditions and the formulation

and implementation of insightful adaptations to those conditions. The element of surprise

provides great competitive advantages in both military and business strategy; information

systems that provide data on opponents’ or competitors’ strategies and resources are also

vitally important.

Of course, a fundamental difference between military and business strategy is that

business strategy is formulated, implemented, and evaluated with an assumption of

competition, whereas military strategy is based on an assumption of conflict. Nonetheless,

military conflict and business competition are so similar that many strategic-management

techniques apply equally to both. Business strategists have access to valuable insights that

military thinkers have refined over time. Superior strategy formulation and implementation

can overcome an opponent’s superiority in numbers and resources.

Both business and military organizations must adapt to change and constantly

improve to be successful. Too often, firms do not change their strategies when their