Page 313 - Sustainability in the Process Industry Integration and Optimization

P. 313

290 Cha p te r T w e l v e

T

160°

80°

45°

150° 10°

160°

ΔH

ΔH 3 ΔH ΔH 2 ΔH 3

1

190°

120° 40°

Reactor

80° 45° 45° 10°

ΔH 2 ΔH 1 Feed

140° Unit 140°

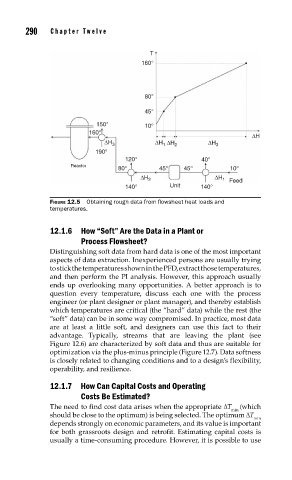

FIGURE 12.5 Obtaining rough data from fl owsheet heat loads and

temperatures.

12.1.6 How “Soft” Are the Data in a Plant or

Process Flowsheet?

Distinguishing soft data from hard data is one of the most important

aspects of data extraction. Inexperienced persons are usually trying

to stick the temperatures shown in the PFD, extract those temperatures,

and then perform the PI analysis. However, this approach usually

ends up overlooking many opportunities. A better approach is to

question every temperature, discuss each one with the process

engineer (or plant designer or plant manager), and thereby establish

which temperatures are critical (the “hard” data) while the rest (the

“soft” data) can be in some way compromised. In practice, most data

are at least a little soft, and designers can use this fact to their

advantage. Typically, streams that are leaving the plant (see

Figure 12.6) are characterized by soft data and thus are suitable for

optimization via the plus-minus principle (Figure 12.7). Data softness

is closely related to changing conditions and to a design’s flexibility,

operability, and resilience.

12.1.7 How Can Capital Costs and Operating

Costs Be Estimated?

The need to find cost data arises when the appropriate ΔT (which

min

should be close to the optimum) is being selected. The optimum ΔT

min

depends strongly on economic parameters, and its value is important

for both grassroots design and retrofit. Estimating capital costs is

usually a time-consuming procedure. However, it is possible to use