Page 206 - Accounting Information Systems

P. 206

CHAPT E R 4 The Revenue Cycle 177

Concluding Remarks

We conclude our discussion of manual systems with two points of observation. First, notice how manual

systems generate a great deal of hard-copy (paper) documents. Physical documents need to be purchased,

prepared, transported, and stored. Hence, these documents and their associated tasks add considerably to

the cost of system operation. As we shall see in the next section, their elimination or reduction is a pri-

mary objective of computer-based systems design.

Second, for purposes of internal control, many functions such as the billing, AR, inventory control,

cash receipts, and the general ledger are located in physically separate departments. These are labor-intensive

and thus error-prone activities that add greatly to the cost of system operation. When we examine com-

puter-based systems, you should note that computer programs, which are much cheaper and far less prone

to error, perform these clerical tasks. The various departments may still exist in computer-based systems,

but their tasks are refocused on financial analysis and dealing with exception-based problems that emerge

rather than routine transaction processing.

Computer-Based Accounting Systems

We can view technological innovation in AIS as a continuum with automation at one end and reengineer-

ing at the other. Automation involves using technology to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of

a task. Too often, however, the automated system simply replicates the traditional (manual) process that

it replaces. Reengineering, on the other hand, involves radically rethinking the business process and

the work flow. The objective of reengineering is to improve operational performance and reduce costs

by identifying and eliminating non–value-added tasks. This involves replacing traditional procedures

with procedures that are innovative and often very different from those that previously existed.

In this section we review automation and reengineering techniques applied to both sales order process-

ing and cash receipts systems. We also review the key features of point-of-sale (POS) systems. Next, we

examine electronic data interchange (EDI) and the Internet as alternative techniques for reengineering the

revenue cycle. Finally, we look at some issues related to PC-based accounting systems.

AUTOMATING SALES ORDER PROCESSING

WITH BATCH TECHNOLOGY

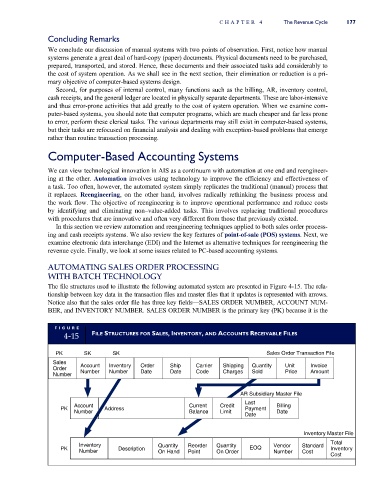

The file structures used to illustrate the following automated system are presented in Figure 4-15. The rela-

tionship between key data in the transaction files and master files that it updates is represented with arrows.

Notice also that the sales order file has three key fields—SALES ORDER NUMBER, ACCOUNT NUM-

BER, and INVENTORY NUMBER. SALES ORDER NUMBER is the primary key (PK) because it is the

FI G U R E

4-15 FILE STRUCTURES FOR SALES,INVENTORY, AND ACCOUNTS RECEIVABLE FILES

PK SK SK Sales Order Transaction File

Sales

Order Account Inventory Order Ship Carrier Shipping Quantity Unit Invoice

Number Number Number Date Date Code Charges Sold Price Amount

AR Subsidiary Master File

Last

Account Current Credit Billing

PK Address Payment

Number Balance Limit Date

Date

Inventory Master File

Total

Inventory Quantity Reorder Quantity Vendor Standard

PK Description EOQ Inventory

Number On Hand Point On Order Number Cost

Cost