Page 437 - Complete Wireless Design

P. 437

Wireless Issues

436 Chapter Ten

Verify that your parts supplier is dependable, since not all components or

RFICs that are in the data books will be truly available—either because they

are preliminary or because they have been discontinued.

Establish that every trace on the PCB is correctly routed, not only to make

sure it reaches the proper board location, but also to avoid unpleasant

coupling effects and EMI.

Validate that all active devices are soldered to the correct terminals

(especially diodes) and that all electrolytics are inserted with the proper

polarity.

Ascertain that components are of the appropriate value, and that they are

correctly and neatly soldered.

All of the above should be performed before turning on the prototype for the

first time to avoid an expensive, embarrassing, and time-consuming ending to

the infamous “smoke test.”

10.8 Antennas

10.8.1 Introduction

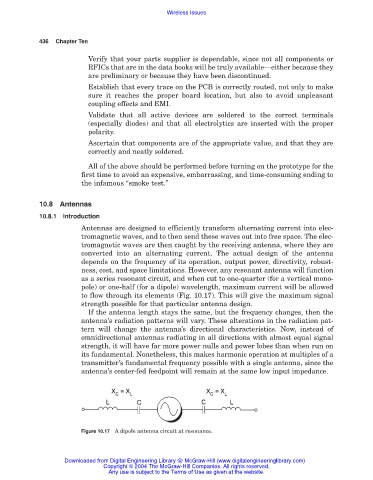

Antennas are designed to efficiently transform alternating current into elec-

tromagnetic waves, and to then send these waves out into free space. The elec-

tromagnetic waves are then caught by the receiving antenna, where they are

converted into an alternating current. The actual design of the antenna

depends on the frequency of its operation, output power, directivity, robust-

ness, cost, and space limitations. However, any resonant antenna will function

as a series resonant circuit, and when cut to one-quarter (for a vertical mono-

pole) or one-half (for a dipole) wavelength, maximum current will be allowed

to flow through its elements (Fig. 10.17). This will give the maximum signal

strength possible for that particular antenna design.

If the antenna length stays the same, but the frequency changes, then the

antenna’s radiation patterns will vary. These alterations in the radiation pat-

tern will change the antenna’s directional characteristics. Now, instead of

omnidirectional antennas radiating in all directions with almost equal signal

strength, it will have far more power nulls and power lobes than when run on

its fundamental. Nonetheless, this makes harmonic operation at multiples of a

transmitter’s fundamental frequency possible with a single antenna, since the

antenna’s center-fed feedpoint will remain at the same low input impedance.

Figure 10.17 A dipole antenna circuit at resonance.

Downloaded from Digital Engineering Library @ McGraw-Hill (www.digitalengineeringlibrary.com)

Copyright © 2004 The McGraw-Hill Companies. All rights reserved.

Any use is subject to the Terms of Use as given at the website.