Page 227 - Designing Autonomous Mobile Robots : Inside the Mindo f an Intellegent Machine

P. 227

Chapter 14

some conditions it may appear to be doing just this, but it must be capable of gather-

ing information from different systems and perspectives and then applying the implied

corrections to the current moment.

Take for example the hypothetical case of an outdoor robot running with lidar and

GPS. Assume that the robot is approaching a tunnel where the GPS will drop out

and the lidar must be used for navigation. Up to the transition point, the GPS may

have dominated the navigation process especially if there were no suitable lidar features.

There will always be some difference between the GPS and the lidar position indica-

tions. During the time when both systems are reporting, it is critically important to

find the true position and heading because of the narrower confines of the approaching

tunnel. If the GPS is reporting 10 times per second, and the lidar is reporting only 3

times per second, then the GPS may dominate navigation until it drops out com-

pletely, without giving the lidar much of a chance. This would not be good, because

if the lidar can see the inside of the tunnel it will have a much higher accuracy in lateral

position and azimuth, and proper orientation in these degrees of freedom is critical for

safely entering the tunnel.

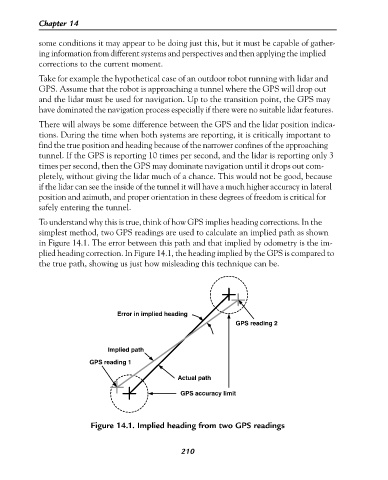

To understand why this is true, think of how GPS implies heading corrections. In the

simplest method, two GPS readings are used to calculate an implied path as shown

in Figure 14.1. The error between this path and that implied by odometry is the im-

plied heading correction. In Figure 14.1, the heading implied by the GPS is compared to

the true path, showing us just how misleading this technique can be.

Error in implied heading

GPS reading 2

Implied path

GPS reading 1

Actual path

GPS accuracy limit

Figure 14.1. Implied heading from two GPS readings

210