Page 215 - Drilling Technology in Nontechnical Language

P. 215

206 Drilling Technology in Nontechnical Language Second Edition

variety of needs, including the following:

1. Physically support the weight of the casing.

2. Prevent fluids from migrating upwards inside the cement, or

between the cement/formation or casing/cement interfaces.

3. Protect the casing against corrosion.

4. Protect the casing against mobile formations.

5. Allow the production casing to be perforated without the cement

shattering under the shock wave.

Mud Removal

One of the most difficult aspects of cementing is to remove all of the

drilling fluid from the annulus so that it can be replaced by cement. In an

in-gauge hole with well-centralized casing, the chances of achieving full

mud removal are good. In an enlarged hole and with the casing not well

centralized, the chances are very poor. Great care is needed in designing

and executing the job.

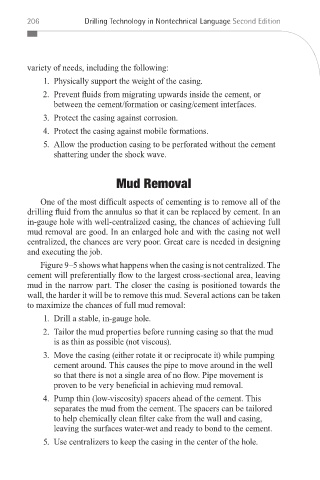

Figure 9–5 shows what happens when the casing is not centralized. The

cement will preferentially flow to the largest cross-sectional area, leaving

mud in the narrow part. The closer the casing is positioned towards the

wall, the harder it will be to remove this mud. Several actions can be taken

to maximize the chances of full mud removal:

1. Drill a stable, in-gauge hole.

2. Tailor the mud properties before running casing so that the mud

is as thin as possible (not viscous).

3. Move the casing (either rotate it or reciprocate it) while pumping

cement around. This causes the pipe to move around in the well

so that there is not a single area of no flow. Pipe movement is

proven to be very beneficial in achieving mud removal.

4. Pump thin (low-viscosity) spacers ahead of the cement. This

separates the mud from the cement. The spacers can be tailored

to help chemically clean filter cake from the wall and casing,

leaving the surfaces water-wet and ready to bond to the cement.

5. Use centralizers to keep the casing in the center of the hole.

09_Devereux.indd 206 1/16/12 3:26 PM