Page 169 - Fundamentals of Ocean Renewable Energy Generating Electricity From The Sea

P. 169

158 Fundamentals of Ocean Renewable Energy

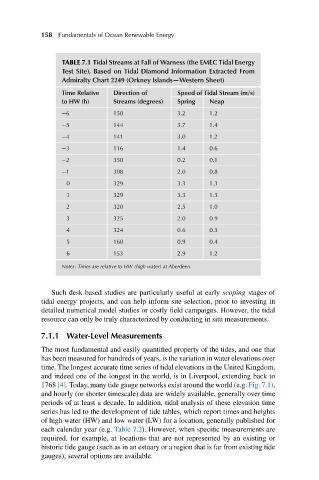

TABLE 7.1 Tidal Streams at Fall of Warness (the EMEC Tidal Energy

Test Site), Based on Tidal Diamond Information Extracted From

Admiralty Chart 2249 (Orkney Islands—Western Sheet)

Time Relative Direction of Speed of Tidal Stream (m/s)

to HW (h) Streams (degrees) Spring Neap

−6 150 3.2 1.2

−5 144 3.7 1.4

−4 141 3.0 1.2

−3 116 1.4 0.6

−2 350 0.2 0.1

−1 308 2.0 0.8

0 329 3.3 1.3

1 329 3.3 1.3

2 320 2.5 1.0

3 325 2.0 0.9

4 324 0.6 0.3

5 160 0.9 0.4

6 153 2.9 1.2

Notes: Times are relative to HW (high water) at Aberdeen.

Such desk-based studies are particularly useful at early scoping stages of

tidal energy projects, and can help inform site selection, prior to investing in

detailed numerical model studies or costly field campaigns. However, the tidal

resource can only be truly characterized by conducting in situ measurements.

7.1.1 Water-Level Measurements

The most fundamental and easily quantified property of the tides, and one that

has been measured for hundreds of years, is the variation in water elevations over

time. The longest accurate time series of tidal elevations in the United Kingdom,

and indeed one of the longest in the world, is in Liverpool, extending back to

1768 [4]. Today, many tide gauge networks exist around the world (e.g. Fig. 7.1),

and hourly (or shorter timescale) data are widely available, generally over time

periods of at least a decade. In addition, tidal analysis of these elevation time

series has led to the development of tide tables, which report times and heights

of high water (HW) and low water (LW) for a location, generally published for

each calendar year (e.g. Table 7.2). However, when specific measurements are

required, for example, at locations that are not represented by an existing or

historic tide gauge (such as in an estuary or a region that is far from existing tide

gauges), several options are available.