Page 242 - Geology of Carbonate Reservoirs

P. 242

DEPOSITIONAL RESERVOIRS 223

SC5 SM1

8000

SC7

8000 gamma sonic

sonic

gamma

CAS1

N 8000

8000

MICROFACIES

Crinoid-Bryozoan gamma sonic

Grainstone-Packstone

RESERVOIR

Crinoid-Bryozoan

Graistone-Packstone 100 FEET

Crinoidal

Wackestone-Packstone

Crinoidal, Spiculiferous, Silty 0 NO HORIZONTAL SCALE gamma sonic

Wackstone-mudstone

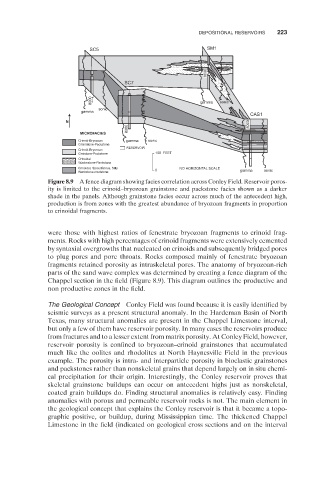

Figure 8.9 A fence diagram showing facies correlation across Conley Field. Reservoir poros-

ity is limited to the crinoid – bryozoan grainstone and packstone facies shown as a darker

shade in the panels. Although grainstone facies occur across much of the antecedent high,

production is from zones with the greatest abundance of bryozoan fragments in proportion

to crinoidal fragments.

were those with highest ratios of fenestrate bryozoan fragments to crinoid frag-

ments. Rocks with high percentages of crinoid fragments were extensively cemented

by syntaxial overgrowths that nucleated on crinoids and subsequently bridged pores

to plug pores and pore throats. Rocks composed mainly of fenestrate bryozoan

fragments retained porosity as intraskeletal pores. The anatomy of bryozoan - rich

parts of the sand wave complex was determined by creating a fence diagram of the

Chappel section in the field (Figure 8.9 ). This diagram outlines the productive and

non productive zones in the field.

The Geological Concept Conley Field was found because it is easily identifi ed by

seismic surveys as a present structural anomaly. In the Hardeman Basin of North

Texas, many structural anomalies are present in the Chappel Limestone interval,

but only a few of them have reservoir porosity. In many cases the reservoirs produce

from fractures and to a lesser extent from matrix porosity. At Conley Field, however,

reservoir porosity is confined to bryozoan – crinoid grainstones that accumulated

much like the oolites and rhodolites at North Haynesville Field in the previous

example. The porosity is intra - and interparticle porosity in bioclastic grainstones

and packstones rather than nonskeletal grains that depend largely on in situ chemi-

cal precipitation for their origin. Interestingly, the Conley reservoir proves that

skeletal grainstone buildups can occur on antecedent highs just as nonskeletal,

coated grain buildups do. Finding structural anomalies is relatively easy. Finding

anomalies with porous and permeable reservoir rocks is not. The main element in

the geological concept that explains the Conley reservoir is that it became a topo-

graphic positive, or buildup, during Mississippian time. The thickened Chappel

Limestone in the field (indicated on geological cross sections and on the interval