Page 95 - Handbook of Adhesives and Sealants

P. 95

Theories of Adhesion 63

example the overlap distances of a lap joint, has diminishing returns.

The next chapter will discuss this possibility.

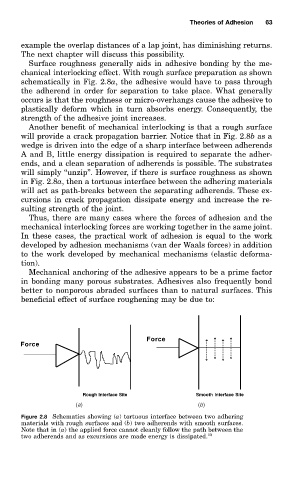

Surface roughness generally aids in adhesive bonding by the me-

chanical interlocking effect. With rough surface preparation as shown

schematically in Fig. 2.8a, the adhesive would have to pass through

the adherend in order for separation to take place. What generally

occurs is that the roughness or micro-overhangs cause the adhesive to

plastically deform which in turn absorbs energy. Consequently, the

strength of the adhesive joint increases.

Another benefit of mechanical interlocking is that a rough surface

will provide a crack propagation barrier. Notice that in Fig. 2.8b as a

wedge is driven into the edge of a sharp interface between adherends

A and B, little energy dissipation is required to separate the adher-

ends, and a clean separation of adherends is possible. The substrates

will simply ‘‘unzip’’. However, if there is surface roughness as shown

in Fig. 2.8a, then a tortuous interface between the adhering materials

will act as path-breaks between the separating adherends. These ex-

cursions in crack propagation dissipate energy and increase the re-

sulting strength of the joint.

Thus, there are many cases where the forces of adhesion and the

mechanical interlocking forces are working together in the same joint.

In these cases, the practical work of adhesion is equal to the work

developed by adhesion mechanisms (van der Waals forces) in addition

to the work developed by mechanical mechanisms (elastic deforma-

tion).

Mechanical anchoring of the adhesive appears to be a prime factor

in bonding many porous substrates. Adhesives also frequently bond

better to nonporous abraded surfaces than to natural surfaces. This

beneficial effect of surface roughening may be due to:

Force

Force

Rough Interface Site Smooth Interface Site

(a) (b)

Figure 2.8 Schematics showing (a) tortuous interface between two adhering

materials with rough surfaces and (b) two adherends with smooth surfaces.

Note that in (a) the applied force cannot cleanly follow the path between the

two adherends and as excursions are made energy is dissipated. 10