Page 197 - Introduction to AI Robotics

P. 197

180

5 Designing a Reactive Implementation

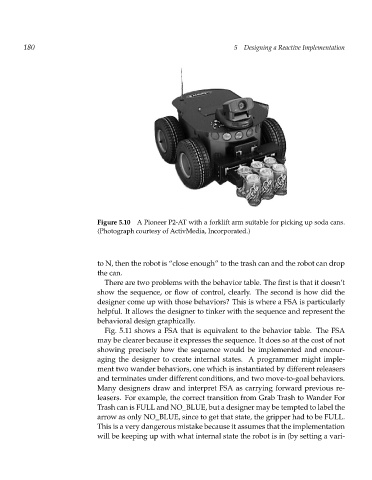

Figure 5.10 A Pioneer P2-AT with a forklift arm suitable for picking up soda cans.

(Photograph courtesy of ActivMedia, Incorporated.)

to N, then the robot is “close enough” to the trash can and the robot can drop

the can.

There are two problems with the behavior table. The first is that it doesn’t

show the sequence, or flow of control, clearly. The second is how did the

designer come up with those behaviors? This is where a FSA is particularly

helpful. It allows the designer to tinker with the sequence and represent the

behavioral design graphically.

Fig. 5.11 shows a FSA that is equivalent to the behavior table. The FSA

may be clearer because it expresses the sequence. It does so at the cost of not

showing precisely how the sequence would be implemented and encour-

aging the designer to create internal states. A programmer might imple-

ment two wander behaviors, one which is instantiated by different releasers

and terminates under different conditions, and two move-to-goal behaviors.

Many designers draw and interpret FSA as carrying forward previous re-

leasers. For example, the correct transition from Grab Trash to Wander For

Trash can is FULL and NO_BLUE, but a designer may be tempted to label the

arrow as only NO_BLUE, since to get that state, the gripper had to be FULL.

This is a very dangerous mistake because it assumes that the implementation

will be keeping up with what internal state the robot is in (by setting a vari-