Page 100 - Introduction to Mineral Exploration

P. 100

5: FROM PROSPECT TO PREFEASIBILITY 83

FIG. 5.8 Typical exploration

trench, in this case on the South

African Highveld.

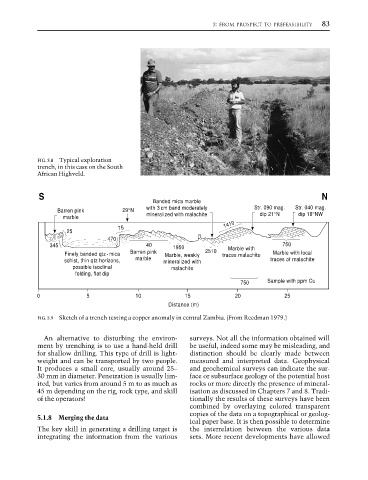

S N

Banded mica marble

Barren pink 29°N with 3 cm band moderately Str. 090 mag. Str. 040 mag.

mineralized with malachite dip 21°N dip 18°NW

marble

1410

75

25

470

345 40 1950 Marble with 750

Finely banded qtz - mica Barren pink Marble, weakly 2510 traces malachite Marble with local

marble

schist, thin qtz horizons, mineralized with traces of malachite

possible isoclinal malachite

folding, flat dip

750 Sample with ppm Cu

0 5 10 15 20 25

Distance (m)

FIG. 5.9 Sketch of a trench testing a copper anomaly in central Zambia. (From Reedman 1979.)

An alternative to disturbing the environ- surveys. Not all the information obtained will

ment by trenching is to use a hand-held drill be useful, indeed some may be misleading, and

for shallow drilling. This type of drill is light- distinction should be clearly made between

weight and can be transported by two people. measured and interpreted data. Geophysical

It produces a small core, usually around 25– and geochemical surveys can indicate the sur-

30 mm in diameter. Penetration is usually lim- face or subsurface geology of the potential host

ited, but varies from around 5 m to as much as rocks or more directly the presence of mineral-

45 m depending on the rig, rock type, and skill isation as discussed in Chapters 7 and 8. Tradi-

of the operators! tionally the results of these surveys have been

combined by overlaying colored transparent

copies of the data on a topographical or geolog-

5.1.8 Merging the data

ical paper base. It is then possible to determine

The key skill in generating a drilling target is the interrelation between the various data

integrating the information from the various sets. More recent developments have allowed