Page 27 - Introduction to Mineral Exploration

P. 27

10 C.J. MOON & A.M. EVANS 1200 3000

Number of discoveries 30 All deposits Production ($ oz −1 ) 1000 Real prices 2500 Production (tonnes)

Giant deposits

Output

25

(> $US 10 billion

800

2000

20

IGV)

1500

600

15

1000

400

10

500

200

0 5 0 1900 1920 1940 1960 1980 2000 0

1940 1950 1960 1970 1980 1990

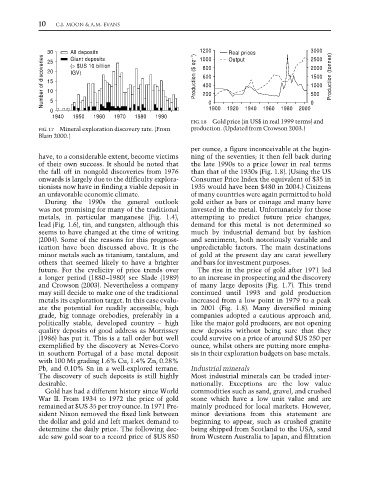

FIG. 1.8 Gold price (in US$ in real 1999 terms) and

FIG. 1.7 Mineral exploration discovery rate. (From production. (Updated from Crowson 2003.)

Blain 2000.)

per ounce, a figure inconceivable at the begin-

have, to a considerable extent, become victims ning of the seventies; it then fell back during

of their own success. It should be noted that the late 1990s to a price lower in real terms

the fall off in nongold discoveries from 1976 than that of the 1930s (Fig. 1.8). (Using the US

onwards is largely due to the difficulty explora- Consumer Price Index the equivalent of $35 in

tionists now have in finding a viable deposit in 1935 would have been $480 in 2004.) Citizens

an unfavorable economic climate. of many countries were again permitted to hold

During the 1990s the general outlook gold either as bars or coinage and many have

was not promising for many of the traditional invested in the metal. Unfortunately for those

metals, in particular manganese (Fig. 1.4), attempting to predict future price changes,

lead (Fig. 1.6), tin, and tungsten, although this demand for this metal is not determined so

seems to have changed at the time of writing much by industrial demand but by fashion

(2004). Some of the reasons for this prognost- and sentiment, both notoriously variable and

ication have been discussed above. It is the unpredictable factors. The main destinations

minor metals such as titanium, tantalum, and of gold at the present day are carat jewellery

others that seemed likely to have a brighter and bars for investment purposes.

future. For the cyclicity of price trends over The rise in the price of gold after 1971 led

a longer period (1880–1980) see Slade (1989) to an increase in prospecting and the discovery

and Crowson (2003). Nevertheless a company of many large deposits (Fig. 1.7). This trend

may still decide to make one of the traditional continued until 1993 and gold production

metals its exploration target. In this case evalu- increased from a low point in 1979 to a peak

ate the potential for readily accessible, high in 2001 (Fig. 1.8). Many diversified mining

grade, big tonnage orebodies, preferably in a companies adopted a cautious approach and,

politically stable, developed country – high like the major gold producers, are not opening

quality deposits of good address as Morrissey new deposits without being sure that they

(1986) has put it. This is a tall order but well could survive on a price of around $US 250 per

exemplified by the discovery at Neves-Corvo ounce, whilst others are putting more empha-

in southern Portugal of a base metal deposit sis in their exploration budgets on base metals.

with 100 Mt grading 1.6% Cu, 1.4% Zn, 0.28%

Pb, and 0.10% Sn in a well-explored terrane. Industrial minerals

The discovery of such deposits is still highly Most industrial minerals can be traded inter-

desirable. nationally. Exceptions are the low value

Gold has had a different history since World commodities such as sand, gravel, and crushed

War II. From 1934 to 1972 the price of gold stone which have a low unit value and are

remained at $US 35 per troy ounce. In 1971 Pre- mainly produced for local markets. However,

sident Nixon removed the fixed link between minor deviations from this statement are

the dollar and gold and left market demand to beginning to appear, such as crushed granite

determine the daily price. The following dec- being shipped from Scotland to the USA, sand

ade saw gold soar to a record price of $US 850 from Western Australia to Japan, and filtration