Page 266 - Low Temperature Energy Systems with Applications of Renewable Energy

P. 266

Geothermal energy in combined heat and power systems 251

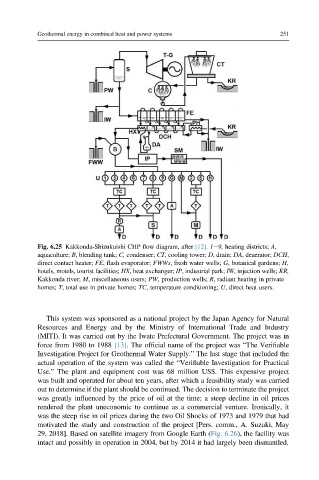

Fig. 6.25 Kakkonda-Shizukuishi CHP flow diagram, after [12]. 1e9, heating districts; A,

aquaculture; B, blending tank; C, condenser; CT, cooling tower; D, drain; DA, deaerator; DCH,

direct contact heater; FE, flash evaporator; FWWs, fresh water wells; G, botanical gardens; H,

hotels, motels, tourist facilities; HX, heat exchanger; IP, industrial park; IW, injection wells; KR,

Kakkonda river; M, miscellaneous users; PW, production wells; R, radiant heating in private

homes; T, total use in private homes; TC, temperature conditioning; U, direct heat users.

This system was sponsored as a national project by the Japan Agency for Natural

Resources and Energy and by the Ministry of International Trade and Industry

(MITI). It was carried out by the Iwate Prefectural Government. The project was in

force from 1980 to 1988 [13]. The official name of the project was “The Verifiable

Investigation Project for Geothermal Water Supply.” The last stage that included the

actual operation of the system was called the “Verifiable Investigation for Practical

Use.” The plant and equipment cost was 68 million US$. This expensive project

was built and operated for about ten years, after which a feasibility study was carried

out to determine if the plant should be continued. The decision to terminate the project

was greatly influenced by the price of oil at the time; a steep decline in oil prices

rendered the plant uneconomic to continue as a commercial venture. Ironically, it

was the steep rise in oil prices during the two Oil Shocks of 1973 and 1979 that had

motivated the study and construction of the project [Pers. comm., A. Suzuki, May

29, 2018]. Based on satellite imagery from Google Earth (Fig. 6.26), the facility was

intact and possibly in operation in 2004, but by 2014 it had largely been dismantled.