Page 204 -

P. 204

MANAGING KNOWLEDGE FOR INNOVATION 193

been created, and rules for its implementation have been defined, the only

problem is to make firms aware of it. Prescriptions about ‘Six-Sigma’ or

‘Customer Relationship Management’ or even ‘Knowledge Management’

as ‘must have’ ‘best’ practices are good examples. Research shows, how-

ever, that this is a misleading and potentially dangerous view (Ettlie and

Bridges, 1987) that greatly downplays the problems of implementation and

the knowledge requirements of innovation. Most innovation is simply not

like that. Box 9.2 summarizes the key limitations of this traditional view.

In Medico, for example, the creation of knowledge went hand in hand with

its use in practice. Indeed the clinical data on the brachytherapy technique

would not be available unless the technique had actually been applied by

medical professionals. In short, knowledge was produced through use, not

before it.

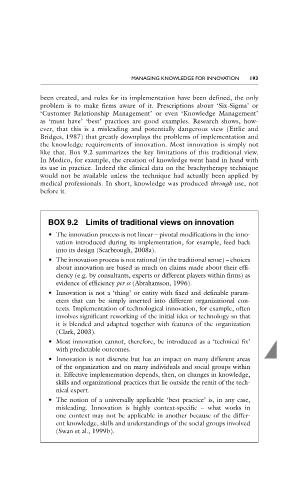

BOX 9.2 Limits of traditional views on innovation

• The innovation process is not linear – pivotal modifi cations in the inno-

vation introduced during its implementation, for example, feed back

into its design (Scarbrough, 2008a).

• The innovation process is not rational (in the traditional sense) – choices

about innovation are based as much on claims made about their effi-

ciency (e.g. by consultants, experts or different players within firms) as

evidence of efficiency per se (Abrahamson, 1996).

• Innovation is not a ‘thing’ or entity with fixed and definable param-

eters that can be simply inserted into different organizational con-

texts. Implementation of technological innovation, for example, often

involves significant reworking of the initial idea or technology so that

it is blended and adapted together with features of the organization

(Clark, 2003).

• Most innovation cannot, therefore, be introduced as a ‘technical fix’

with predictable outcomes.

• Innovation is not discrete but has an impact on many different areas

of the organization and on many individuals and social groups within

it. Effective implementation depends, then, on changes in knowledge,

skills and organizational practices that lie outside the remit of the tech-

nical expert.

• The notion of a universally applicable ‘best practice’ is, in any case,

misleading. Innovation is highly context-specifi c – what works in

one context may not be applicable in another because of the differ-

ent knowledge, skills and understandings of the social groups involved

(Swan et al., 1999b).

6/5/09 7:20:35 AM

9780230_522015_10_cha09.indd 193 6/5/09 7:20:35 AM

9780230_522015_10_cha09.indd 193