Page 172 - Pressure Swing Adsorption

P. 172

146 PRESSURE SWING ADSORPTION EQUILIBRIUM THEORY 147

In this case the power cost has been reduced by 37%, and the adsorbent cost lead to composition and thermai waves that propagate toward the product

has been reduced b}' 13%. In addition, this system does not require a vacuum end of the column. For many PSA applicat1ons, these fronts comcide, and the

oumo or as many valves (e.g., for blowctown m successive stages), so the

induced temperature shifts Just due to adsorotwn are often greater than

entire system 1s s1moler and less expensive. A final, subtle 001nt that has not l0°C and may exceed 50°C (Garg and Yon 29 ). It 1s shown iater that

been taken into account 1s that the cycle time could possibly be reduced for temperature shifts dunng a typical PSA cycle need not significantly affect the

this case (smce less uotaKe and release occur), which would lead to less adsorption select1v1ty, even though relatively large changes m absolute capac-

reQmred adsorbent, and a further reduction m cost. ity may occur. For systems with small amounts of a strongly adsorbed

contaminant or·a very weakly adsorbed carrier, however, the thermal wave

, may lead the composition wave (see Section 2.4) anct 111 such cases the

adsorption seiect1v1ty can be drarnat1cally affected.

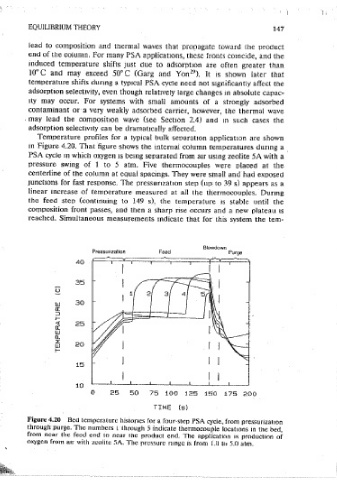

4.8 Heat Effects Temperature profiles for a typical bulk seoaratmn application are shown

m Figure 4.20. That figure shows the internai column temperatures dunng a

The. term heat effect 1s frequently applied to a conspicuous change m PSA cycle m which oxygen 1s bemg separated from air usmg zeolite 5A with a

performance that coincides with a temperature fluctuation. Although the pressure swing of 1 to 5 atm. Five thermocouples were olacect at the

term 1s introduced here, 1t 1s covered more quantitatively m Section 5.4. centerline of the column at equal spacings. They were small and had exposed

Viewing a packed bed oressure swing adsorotton system, there are two roam Junct10ns for fast response. The pressunzat1on step (up: to 39 s) appears as a

heat effects: heat 1s released as a heavy coriioonent displaces a light compo. linear increase of temperature measured at all the thermocouples. Durmg

nent due to the preferential uptake, and compression raises the gas tempera- the feed step (contmuing to 149 s), the temperature JS stable until the

ture. Of course, heatmg due to adsorpt10n and compress10n 1s at least cornoosition front passes, and then a sharp nse occurs and a new oiateau 1s

partially reversible, since desorption and deoressurization both cause the reached. Simultaneous measurements indicate that for this system the tern•

temoerature to drop. The relative magmtuctes of such temperature swings are

affected by heats of adsorption, heat capacities, and rates of heat and mass

transfer. Hence, the potential effects on performance are many, and they

Btowdown

deoend on operating conditions, Properties, and geomet,ry, sometimes m Pressurization Feed Purge

comolicated ways. For examnle, at a constant pressure, a cycle of adiabatic 40

adsorption followed by adiabatic desorption involves less uptake and release

than the isothermal counterpart. As a result, one might expect poorer 35

oerformance from an adiabatic system as opposed to an isothermal system, u

but that is not necessarily true for PSA, as shown later. 1 2 3 4 5

The term heat effects has aComred a connotation of mystery and confu- w 30

a:

sion. This is especially true in the field of PSA since many different effects :,

.,

r

Occur s1mt.iitaneouSly. ·Thus, determmmg cause-and•effect relationships ts not 25

a:

t'riviai. In fact, some unusual thermal behavior was revealed m a patent w

0.

disclosure hy Collins 28 that continues to perplex some mctustnal nractition• ::E 20

w

Crs. Collins stated that, "Contrary to the pnor art teachings of uniform ....

adsorbent bed temperature during pressure swing air seoaration, 1t has been

unexoectedly discovered that these them1ally isolated beds experience a 15

sharpiy deoressect temperature zone m the adsorot1on bed mlet end .... The

temperature depression hereil1.before ·described does not occur m adsorbent 10

beds of less than 12 inches effective diameter." Without attempting to 0 25 50 75 100 125 15U 175 200

unravel those observations, it may be instructive to consider what happens in

TIME (s)

a small coiumn, to see detailed effects directly and to mfer their causes, anct

to become aware of the range of potential effects. ~igure 4.20 Bed temperature histories for a four-step PSA cyde, from pressurization

For most systems, the principal heat effect anses from simuitaneous axial through purge. The numbers l through 5 indicate thermocouple locatmns m the bed,

from near the feed end m near the product end. The opplkatmn is production of

bulk How, adsorption, and heat release due to adsorption. These phenomena

oxygen from air with zcoiite 5A. The pressure range 1s from 1.0 t/J 5.0 atm.